Scholarly research on Shakira has focused on image-building and the singer’s transnational performances since the crossover from the Latin American market to global mainstream in 1999 to 2001. In contrast, this essay drives attention to the sound of her songs demonstrating how the singer’s vocal expression changed when she started singing in English. The song “Ojos así,” its various recordings and especially the translation entitled “Eyes Like Yours” are subjects of analyses. Additionally, an overview of the albums released since 2001 indicates that the singer serves the Spanish-speaking and English-speaking markets with diverse (vocal) performances, and multilingualism as well as translation form an important part of Shakira’s artistic production.

[Download PDF-Version] | [Abstract auf Deutsch]

Introduction

In 2001, the release of Shakira’s first English language album Laundry Service started her global career, making her one of the most famous mainstream singers in the world. Today, Shakira is known worldwide for performing the official song “Waka Waka” for the FIFA World Cup 2010 in South Africa, and for her performance in the Super Bowl Half Time Show together with Jennifer Lopez in 2020. In academic writing, the singer is recognized for her transnational performances (Gontovnik 2010), a certain deracination when entering the global market (Fuchs 2007, Cepeda 2010), and the subsequent reintegration of her Caribbean origins into her image (Celis 2012), which is especially manifest in the media coverage and the official music videos.

Research generally focuses on her chart hits with English lyrics, while her songs with Spanish lyrics are studied less frequently, although they form half of Shakira’s repertoire. Though some authors have mentioned Shakira’s multicultural background and multilingualism (Fuchs 2007, 171; Cepeda 2010, 74), the way different languages are represented in her music has not yet been analyzed in detail. However, it is impossible to ignore that the singer utilizes interlingual and other forms of translation as a means of reaching diverse audiences, and as a powerful tool for positioning herself in the global as well as local Latin American pop music market. As a result, different languages shape the sound of her songs.

According to Umberto Eco, translation (be it interlingual translation from one language to another, or respectively, transmutation which is the adaptation between semiotic systems, such as literature, music, the visual, etc.) may be understood as negotiation; polysemy and substance in the original always become lost, while translators normally add something depending on their interpretation, aesthetics, and abilities. Through rewriting, translations gain new meanings and forms in their new contexts. Words in another language change the substance of speech, including rhythm, sounds of the vowels, and consonants or rhyme (Eco 2003). Consequently, the translation of poetry is especially complicated because of those changes in substance. Poems set to music as songs are even more determined and offer more pitfalls to translators. Nevertheless, popular songs are frequently transferred to new audiences and translated or adapted freely, in some cases with great success, as Isabelle Marc has shown in her examination of “travelling songs” (Marc 2015).

As part of my research on the translation of vocal music, [1] Shakira’s oeuvre serves as a rich source of song translations with recordings in various languages and situations, such as studio productions or live concerts. This article is a preliminary case study that summarizes Shakira’s reasons for starting song production in the English language around the turn of the century in the context of her changing image alongside global success. The following analysis of different tracks and performances of the song “Ojos así,” translated as “Eyes Like Yours,” aims to demonstrate: (1) which aspects of the song were substantially changed in this process and provoked the criticism by reviewers and Latin/o American fans; (2) which parameters of the sound of Shakira’s voice were lost; and (3) which elements of bodily performance were instead added in on-stage performances. The comparison reveals how Shakira interpreted the song and rewrote it several times through various performances, leading up to the most recent performance at the Super Bowl Half Time Show 2020 which displayed the song’s very essence in only few seconds.

In contrast to most writings on Shakira that focus on her physical appearance, stardom, and the music videos, this article provides insights into the variations of sound and musical performance in both studio and live recordings published on CD or DVD. The first section examines Shakira’s position in the historical occurrences of the translation boom in Latin/o pop music. Phono-musicological methods, i.e. the study of recorded music, form the core of the argumentation in the second section in order to drive attention to a particular song and the music itself, whose details have rarely been analyzed sufficiently in academic writing about the singer. In the third section, a glance at Shakira’s productions after the album Laundry Service emphasizes the calculated performance of multilingualism and sound in her oeuvre that guaranteed her position as a successful singer in Anglophone mainstream as well as Latin American pop.

The “Miamization” of Latin American Pop and the Release of Shakira’s Album Laundry Service (2001)

Shakira became a successful singer in Latin America with the Spanish-language albums Pies descalzos (1995, produced by Luis Fernando Ochoa) and Dónde están los ladrones? (1998, produced by Emilio Estefan Jr., Lester Méndez, and Luis Fernando Ochoa), both released by Sony Colombia. These recordings sold several million units. Shakira appeared as a dark-haired girl on CD covers, often wearing small braids and long leather clothes in live performances. With Dónde están los ladrones?, she reached the U.S. market and, in January 1999, she first appeared on Rosie O’Donnell’s TV show on NBC, where she performed the song “Inevitable” in an English translation. At the time, her success was part of a general adaptation of Latin American music to the U.S. market, which was accompanied by a growing bilingualism of the performers and the repertoire. This phenomenon was termed “Miamization” by Daniel Party (2008) due to the fact that the production of Latin American pop music had almost completely moved to Miami.

Regarding Latin American music’s breakthrough to the global market at the end of the 1990s, Party traces its roots back to the music of Emilio Estefan Jr.’s band Miami Sound Machine, and more specifically its album Primitive Love (1985), as well as to the creation of the Best Latin Pop Performance category at the 1984 Grammy Awards (Party 2008, 66–67). María Elena Cepeda recalls that, of course, there are other predecessors of the Latin/o music boom during the 20th century and she mentions the music entrepreneur Victoria Hernández or “veteran performers” such as Susana Baca or Rubén González (Cepeda 2001, 70). In the 1990s, Emilio Estefan Jr. became the most famous and powerful producer of Latin/o American artists, working with such interpreters as his wife Gloria Estefan, Ricky Martin, Marc Anthony, and Jennifer Lopez. At the same time, Miami had become not only a “transnational economic center,” but the “heart of Latin American show business and the preferred production center for Latin American pop artists wishing to internationalize their career, either within Latin America or crossing over to the American market” (Party 2008, 65).

The Latin/o pop boom in 1999 drove attention to the centrality of Emilio Estefan Jr. The biggest Latin/o hits of the year were produced by him and his parent company Sony. Ricky Martin was awarded a Grammy for his album Vuelve and published his first album in English, Ricky Martin. Carlos Santana (Supernatural), Marc Anthony (Marc Anthony), and Jennifer Lopez (On the 6) released albums that sold millions and attained multiple platinum status in the U.S. Martin and Anthony anglicized their names in the early stage of their careers, but performed successfully as “white-skinned, good-looking” (Fiol-Matta 2002, 32) singers on the Spanish-speaking music market. In 1999, bilingualism became a fundamental principle of their stardom. The English-language albums Ricky Martin and Marc Anthony also included two or three songs in Spanish versions, and Martin’s hit single “Livin’ la Vida Loca” directly mixed English with Spanish words.

Shakira profited from the Latin/o boom in 1999 and was at the same time an important part of it. In April, she repeated “Inevitable” in English at the American Latino Media Arts Award in Pasadena, and in August, she performed an entirely Spanish Unplugged concert for MTV which was recorded and released on CD and DVD. Shakira started working on an English translation of Dónde están los ladrones?, as she stated during the O’Donnell show. In the second half of the year 1999, the singer changed her management from Emilio Estefan Jr. to Freddie DeMann, the former manager of Michael Jackson and Madonna. In November 1999, she appeared in Cartagena for the election of Miss Colombia with newly-dyed blonde hair with smooth braids. In the following year, she still performed her Spanish songs but appeared with the new image on her “Anfibio” tour as well as at the Latin Grammys, where she was awarded Best Pop Singer for the song “Ojos así.”

Video 1: Shakira performing on her Anfibio Tour in 2000, 0:58–1:13.

Video 2: Shakira performs “Ojos así” at the first Latin Grammys in 2000

Both on the tour and at the Grammy Awards, staging and dancing became the focus of that song—a tendency that can also be observed in later stage performances. Shakira’s dance and body moved into the foreground when entering “the multilingual market” (Celis 2012, 201) and her dance style became more professional. Since then, album covers often show her sparsely dressed with blonde, curly hair. The singer obviously worked as intensively on her bodily appearance as on the production of new songs. In 2000, she rejected the idea of translating the whole album Dónde están los ladrones? and, for several months, dedicated herself to the composition of new songs for her upcoming English album Laundry Service instead. According to the press and fan literature, she found writing texts in English and translating more difficult than expected and needed more time to find her way (Diego 2001, 128–29). From her statements, it can be deduced that she recognized the difficulties of translation. With the help of her new management and various co-writers she became more “anglicized” (Cepeda 2010, 72): her body became thinner, her hair became blonder, and her songwriting adapted to the new language.

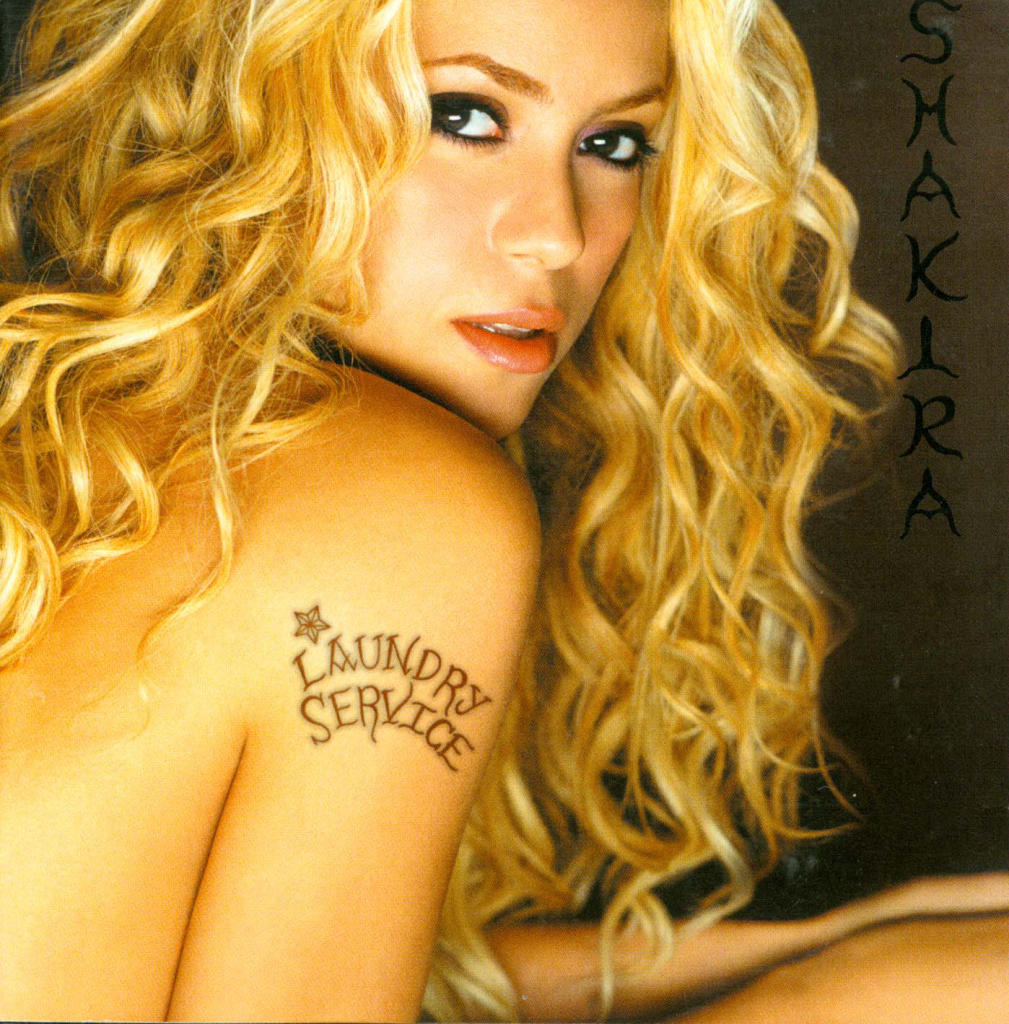

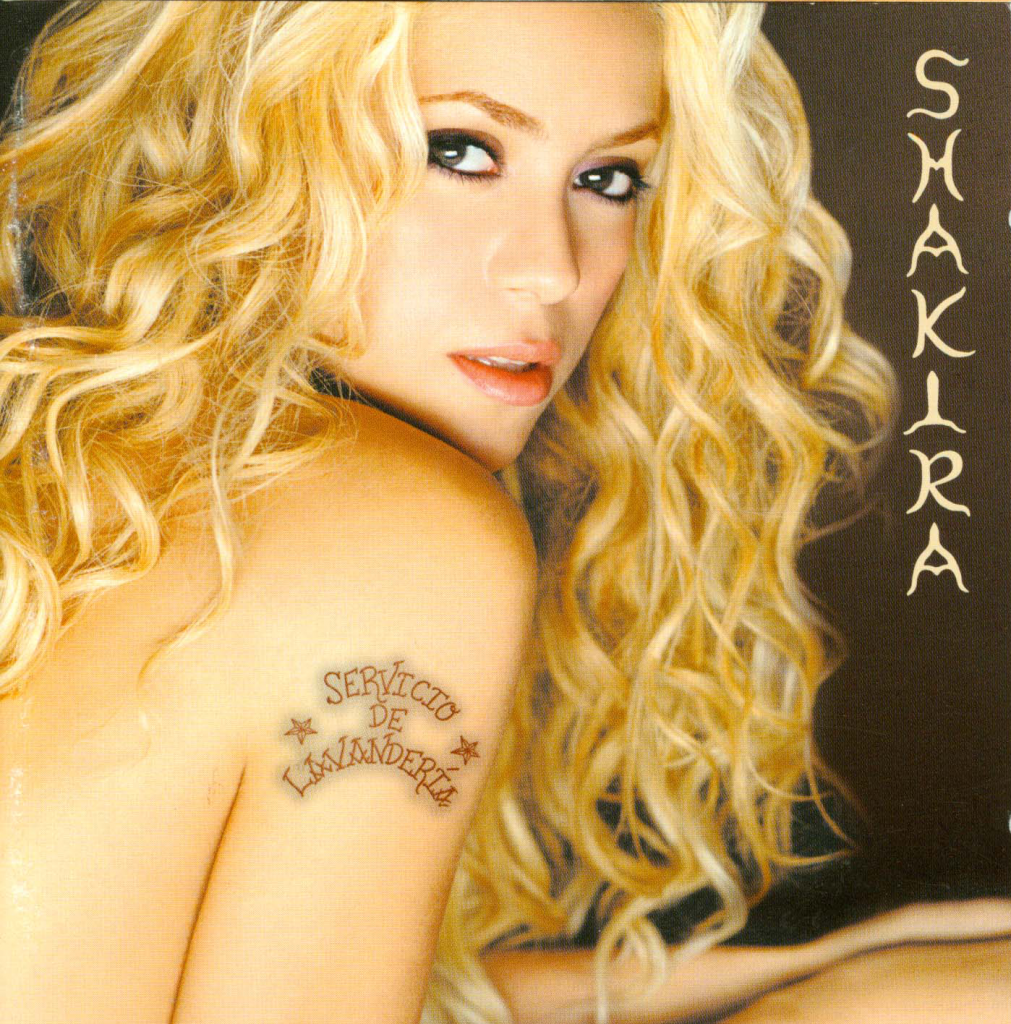

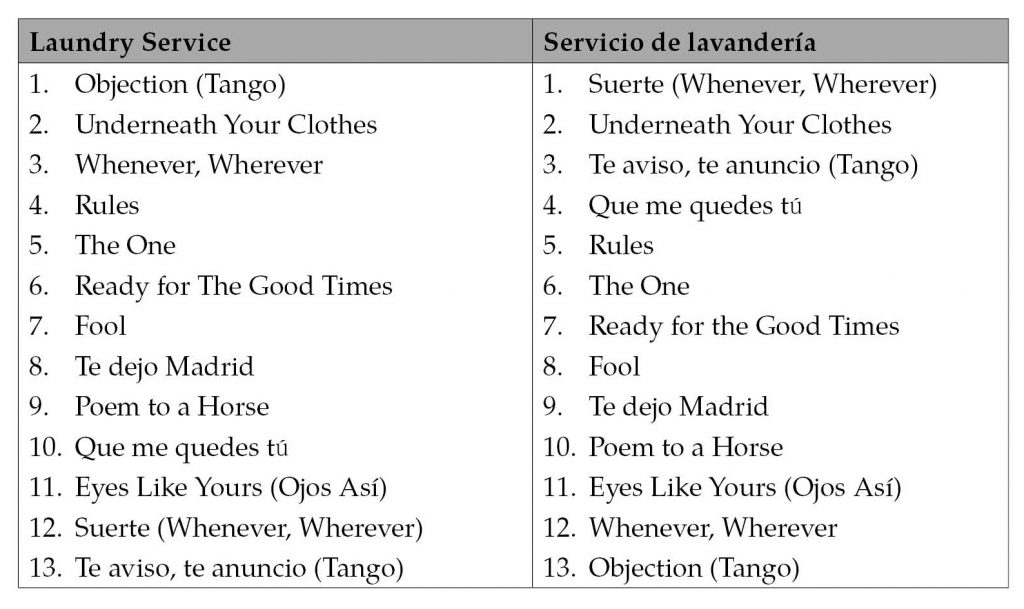

In 2001, Laundry Service was released by Sony/Epic. It contained nine songs in English and four in Spanish—almost exclusively newly composed titles. Songs that were both produced in English and Spanish versions were the tango “Objection” (“Te aviso, te anuncio”), and “Whenever, Wherever” (“Suerte”). The only older song on the CD was “Eyes Like Yours,” the translation of “Ojos así.” Gloria Estefan, who had performing experiences in both English and Spanish, helped with the translation and is credited for the lyrics. Interestingly, the Spanish edition, Servicio de lavandería, appeared in a slightly brighter cover: Shakira’s body seems even more bleached than on the cover of Laundry Service, which might have additionally stimulated the negative reaction of many Latin/o American fans to the new image (Cepeda 2010, 72). The order of the tracks on Servicio de lavandería is different when compared to Laundry Service, and starts with the Spanish version of “Whenever, Wherever.” However, there was no additional track for the Spanish-speaking audience, as is the case in later albums.

Fig. 1 & 2: Cover of “Laundry Service” and “Servicio de lavandería” (Sony Music Entertainment 2001, art direction: Shakira and Ron Jaramillo, photographer: Firooz Zahedi, graphic artist: Michelle Holme / Sara Syms)

Despite commercial success, with more than 15 million units sold worldwide, Shakira’s change of language and image was controversial after the release of Laundry Service in 2001. The term “anglicized” was often used pejoratively. In November 2001, Rolling Stone reviewer Ernesto Lechner evaluated the album under the headline, “Latin Rock Superstar Gets Lost in Translation”:

On the Spanish-language albums that elevated her to Latin-rock-goddess status, Shakira Mebarak sounded playful, bohemian and rebellious. On her English-language debut, she sounds downright silly, but the blame is not entirely hers. Surrounded by a battalion of producers and songwriters, the twenty-four-year-old yodeling diva can’t quite overcome the pedestrian nature of most of the material at hand, the bulk of which she co-wrote. Equally misdirected are her efforts to spice things up with obvious touches of Latin American folklore (the opening “Objection” sounds like a cross between “Livin’ la Vida Loca” and an Astor Piazzolla tango). Shakira’s voice is a wild and beautiful instrument, and she’s capable of delivering scorching moments of musical passion, as her live performances have amply demonstrated. But if you take away the Zeppelin-esque crunch of the Glen Ballard-penned ballad “The One” and the sinuous chants of the Lebanese-flavored “Eyes Like Yours,” you’ll see that, for now, at least, Shakira’s magic is lost in translation. (Lechner 2001, 126)

It seems that Lechner blames the compositions and arrangements for the loss of “magic” on the one hand, while other phrases such as “sinuous chants” or “Shakira’s voice is a wild and beautiful instrument” suggest that he also attributes it to a changed voice. Lechner is not analytical enough to keep both layers apart. The fact that he mentions “The One” and “Eyes Like Yours” as outstanding is noteworthy. Equally, Elizabeth Mendez Berry judged in Vibe that “Eyes Like Yours” was one of the better tracks on Laundry Service. She also referred to Shakira’s performance of “Ojos así” at the Latin Grammy Awards and the way it amazed the audience:

When Shakira took the stage at the Latin Grammys last year and performed her hit “Ojos Asi,” the Colombian pop princess seemed to translate perfectly. She enchanted folks who don’t speak Spanish but do understand feminine writhing. […] Laundry Service mines the unthreatening alt-pop territory that made her a star. But while her Spanish-language albums sparkled with elegant wordplay, this record is rife with clichés, both musically and lyrically. Featuring the obligatory tepid dance-floor track, and mildly Middle Eastern songs—the most vigorous of which is “Eyes Like Yours,” a translation of “Ojos Asi”—Laundry [sic!] is seldom inspired. Indeed, the four Spanish-language tracks are the highlights, including boppy guitar-and-harmonica numbers and Caifanes-esque melancholy ballads. For Anglophone Latin lovers, Shakira’s lyrics are best left to the imagination. (Berry 2001, 18)

Both critics argued that Shakira’s “magic” was lost because the English lyrics and music were too stereotypical, less original or authentic than her older songs, but the reviews remained rather superficial and did not really explain the reasons for this impression. Interestingly, both refer to translation from different angles: Berry suggests that in a concert or show, no interlingual translation is necessary. As long as bodily performance enchants the audience, lyrics do not need translation or to be understood. In contrast, when referring to the overall shift from Spanish to English, Lechner, as well as Berry, detects less quality of the lyrics, the music, and the overall impression—always comparing them with Shakira’s former productions. Apparently, none of the authors accepted the changed aesthetics of Laundry Service and while this attitude was probably shared with Latin American fans, the album was successful with listeners around the globe who were not previously familiar with the singer. Curiously enough, despite their profound skepticism towards the transfer from Spanish to English, both critics emphasized that “Eyes Like Yours” was one of the best songs of the album, although this song is the oldest one, only translated and profoundly changed in terms of vocal expression.

Changes in Substance: A Comparison of “Ojos así” and “Eyes Like Yours”

“Ojos Así” […] kicks double butt in English, but back in Spanish on Dónde Están los Ladrones? it kicks quadruple butt. It’s the identical track except for the voice; the difference is that in English her voice slices around making lightning-brilliant treble strokes in the air above the instruments, whereas in Spanish she’s got a deeper timbre and richer tone and so is in with the rest of the music, and her voice moves with the whole force of the sound, hence there’s more force total. In English she’s, so to speak, dressing herself up in an alternative personality, and maybe her new hairstyle is part of this too. (Kogan 2001)

Frank Kogan’s review of Laundry Service in the magazine Village Voice is exceptional in giving more attention to Shakira’s voice in English and Spanish with special regard to “Ojos así.” These observations are rich in associations and describe the vocal effect in a fruitful, subjective way. That is why the quote is an ideal starting point for analyzing the tracks. Nevertheless, the critique could be developed more empirically in order to describe the musical effects in more detail. The following analysis aims to complement Kogan’s statements with a general overview of versions of the song and changes in vocal and bodily performance over the course of time. Kogan is right in comparing “Eyes Like Yours” from Laundry Service with “Ojos así” from Dónde están los ladrones?, but between 1998 and 2001 other performances, such as the single version, the MTV Unplugged performance, or the Latin Grammy show obviously influenced the audience’s perception of the song as illustrated in Berry’s review. My comparison aims to value the variations in Shakira’s musical performance and to make evident the translation efforts, successes, and failures on various levels.

The album and the single version of “Ojos así” included in Dónde están los ladrones? as track 11 and 13 are relatively similar;tempo (126 beats per minute), overall form, and total length do not differ. The contrast is in the instrumentation. In the single version’s intro, a solo string instrument plays microtonal ornamentations and vibrato at the beginning, evoking Middle Eastern music styles, while the regular album version starts with a less ornamented duo of violin and accordion. The vocal tracks hardly vary; the vocal layer even seems to be identical, though the overall mix is a bit different. As it does not alter the voice, the single version track will not be included in the following comparison of the vocal expression.

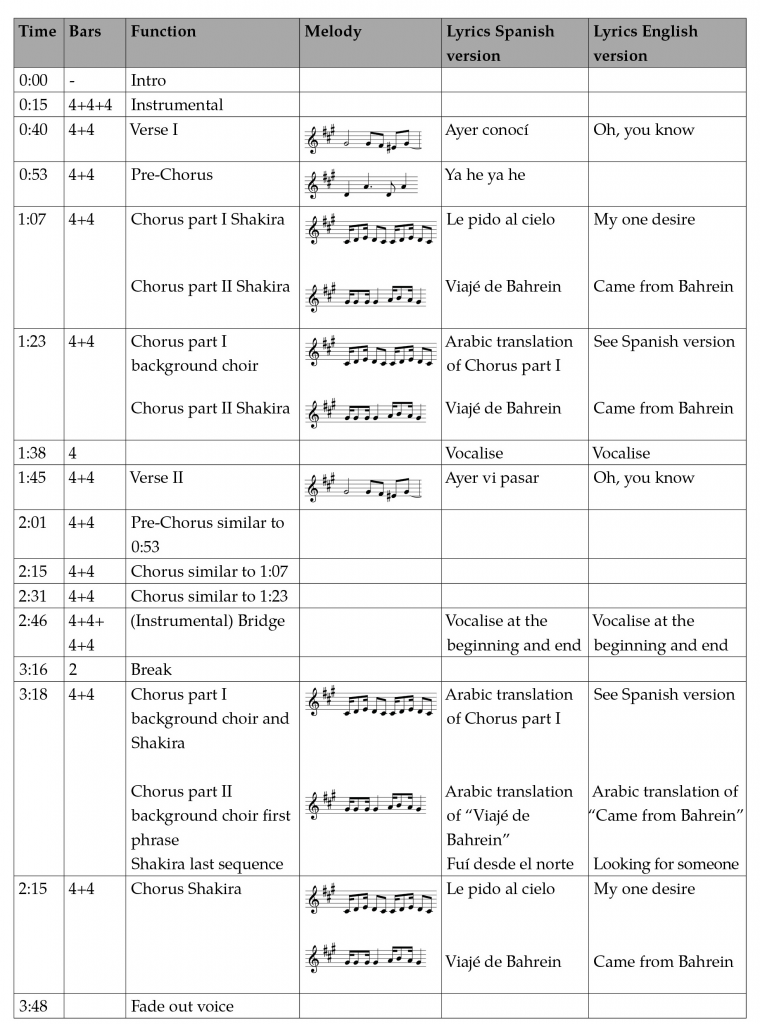

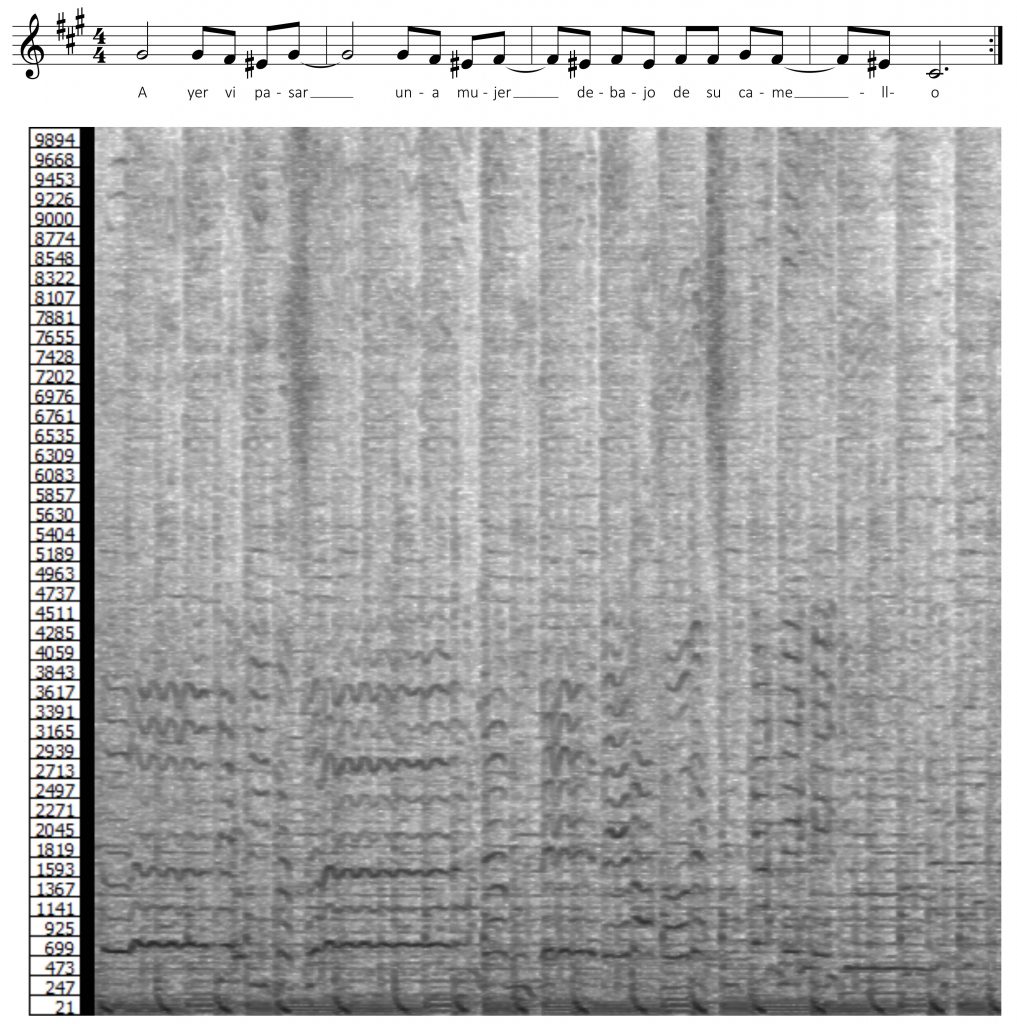

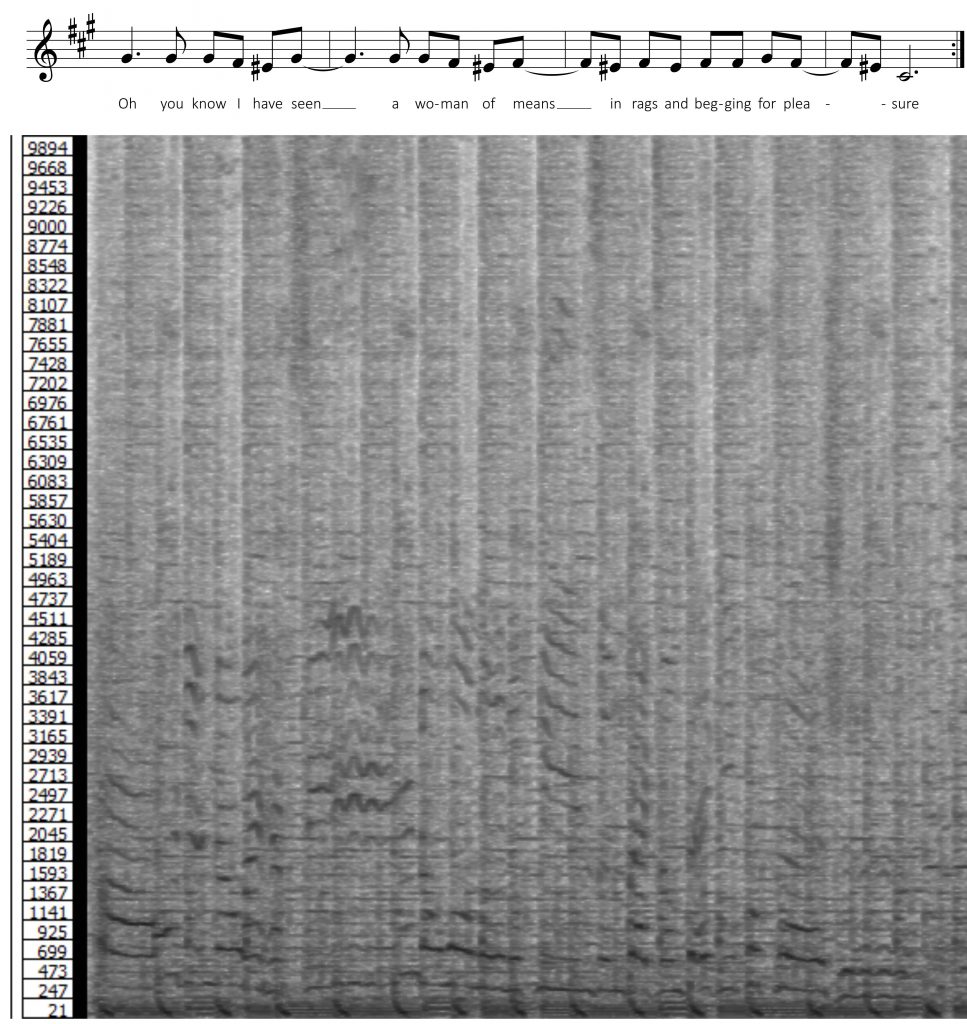

The overall form of the 1998 (Spanish) and 2001 (English) recordings is a verse/pre-chorus/chorus form with an instrumental bridge instead of a third verse and pre-chorus (see Fig. 4). An interesting feature is the use of Arabic lyrics in the repetition of the first chorus line in the background and in Shakira’s final chorus. Due to the use of Arabic, the song is bilingual and works with the sounds of the language, which is not understood by many listeners. Other elements that arouse the listener’s attention are segments of either two or four bars and the instrumental twelve bars beginning, all of which break up the regular eight-sixteen-periodicity. Every beat is clearly accentuated according to the 4-to-the-floor principle. The melody follows a Phrygian scale over C-sharp (C# D E F# G# A B C#). Except in the chorus, the third step is mostly raised resulting in a Phrygian dominant scale (C# D E# F# G# A B C#). Together with the percussion instruments darbuka, riqq, and others played by dancer, choreographer, and percussionist Myriam Eli, these aspects add up to a music that perfectly fits to the Middle Eastern atmosphere described by the lyrics.

For the 2001 English translation, the instrumental background is identical to the Spanish album track, although everything is mixed a bit differently and the credits are not completely provided in the booklet. Of course, the vocal was recorded in English so that in “Eyes Like Yours” Shakira’s voice blends in less with the instruments when compared to the Spanish original.

Between the 1998 Spanish recording and the 2001 English version, the song was reworked for the MTV Unplugged concert in 1999. There is a longer, detailed introduction and before the final chorus, a drum-based sequence is introduced while Shakira dances, as can be seen in the corresponding video recording (released in 2002). In the final chorus, Shakira’s Arabic vocals were removed and in return greater emphasis was given to (belly) dance, which is easier to appreciate than a foreign language—as Berry puts it, “feminine writhing” translates “perfectly” (Berry 2001, 18, see above). Given the different placement of the microphones and the instrumentation in the Unplugged performance, her voice clearly comes to the foreground in this recording. Finally, there is less compression in this track than in the other versions, which makes the song smoother and less suitable for playing in a dance club setting.

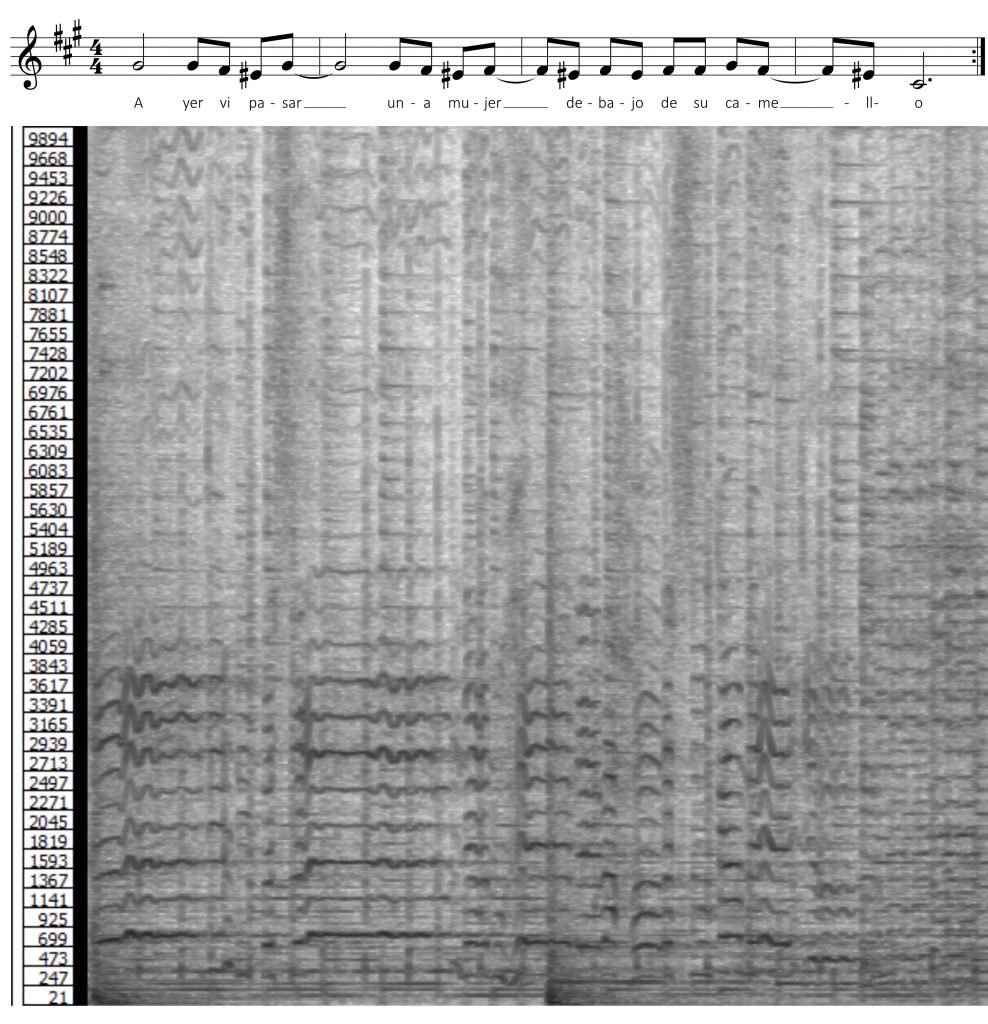

Besides the various recording situations and arrangements, the differences in the vocal performance are the most impressive when comparing the Unplugged version from 1999 to the 1998 Spanish and 2001 English recording. For example, in the beginning of the second verse (Fig. 5–7), the long vowels [a], [o] and [u] are sustained with an irregular vibrato in both Spanish versions. On the unplugged recording this becomes even more obvious. In the English translation, the vibrato becomes shorter due to more syllables in the lyrics: There are more words, letters and, finally, notes to sing:

Ayer vi pasar una mujer debajo de su camello

un rio de sal un barco abandonado en el desierto

Oh, you know I have seen a woman of means in

rags and begging for pleasure

crossed a river of salt just after I rode a ship that’s sunk in the desert

In compensation for the vibrato, there are other new effects in the English version, for example the glissando down from the first note (this might be the effect Kogan termed “lightning-brilliant treble strokes in the air”; Kogan 2001). Moreover, Shakira’s Spanish is characterized by noisy consonants, especially the [s]—a feature that is rather missing in English. These characteristics are visualized in the spectrograms (Fig. 5–7).

The Spanish recordings often show intense frequencies (a formant) around 3,000 Hz and, especially when Shakira sings vowels like [u] or [o], between 7,000 and 10,000 Hz, which constitute the characteristic timbre and rich tone of her voice. The sound of Shakira’s voice might have been processed electronically to comply with certain aesthetics, and frequencies might be highlighted artificially, but in any case, it is characteristic of the final product. These frequencies are less present in the English version, which might be due to less [u] or [o] vowels or different use of the equalizer. The passages where Shakira sings vocalises are rather similar in the Spanish and English versions, though the voice is significantly more in the foreground of the mix in the Spanish one.

Another important element that changed in the English lyrics is the position of the hook line at the end of the chorus. In the Spanish version, the two final chorus verses read “No encontré ojos así / Como los que tienes tú” (literally: “I didn’t find eyes / like those you have”). The words of the song’s title “Ojos así” form the end of the penultimate verse. The seven syllables of the last verse are set as a descending motive in seconds that repeats three times (E–D, E–D, E–D) before reaching the final C-sharp and forming a hook that can be easily sung. Although, in the English version, the song’s title “Eyes Like Yours” is placed at the very end of the chorus as a typical hook, the complete two verses read “tearing down windows and doors / and I could not find eyes like yours”, which makes singing along more complicated, it loses some clarity in the combination of words and melody, and results in Shakira’s voice not being “in with the rest of the music” (Kogan 2001).

It becomes clear in this comparison that the new language did not fit exactly with the melody and slight changes were necessary. It seems that the recording gives an idea of the problems Shakira was faced with when adapting her older songs to the new language. Despite the losses in substance and sound (namely, the overtone spectrum), “Eyes Like Yours” served as a bridge between the old Latin American and the new “anglicized” Shakira as the reviews of Berry and Lechner display. Although the song’s outstanding instrumentation kept working with the English lyrics, it was only half as convincing to reviewers. One might ask whether the transformation of the voice’s performance and sound happened by accident, was intended as a kind of adaptation to the new audiences, or a mix of both. Even though this question can probably only be answered by interviews with the singer and the production team, the later handling of the song shows which elements of it were negotiated and further transformed in the course of time.

After the release of Laundry Service, Shakira mainly performed “Ojos así” in Spanish and there are hardly any other English versions. “Ojos así” remained an important element of her live shows, performed either at the beginning (“Tour of the Mongoose” 2002–03) or in the final part (“Oral Fixation Tour” 2006–07, “The Sun Comes Out World Tour” 2010–11) of the shows. Beginning with the Latin Grammy show in the early 2000s, the formal structure followed the unplugged version from 1999, where it was changed in overall form by giving more importance to dance rather than to voice. For example, in the Live from Paris video recording (2011), the lyrics are reduced to the first verse and chorus. The vocalise after the first chorus directly leads to the instrumental bridge and to the extended, softer percussive passage with subsequent violin solo and Shakira’s dance. Her belly dance movements still show the characteristics which were introduced during the MTV concert in 1999, choreographed and taught by Myriam Eli, but had been exercised more professionally over the course of time since the Latin Grammy performance.

In the Super Bowl Halftime Show 2020, the song was reduced to only the first phrase of the lyrics in Spanish with much ornamentation, vibrato, and reverb in only ten seconds, followed by a belly dance sequence lasting twenty seconds, which served as a prelude to the next song “Whenever, Wherever”. Indeed, the use of a rope, the dress, and the movements resemble the dance sequence before “Whenever, Wherever” rather than the staging of “Ojos así” at the “Oral Fixation Tour”. Thus, the very essence of “Ojos así” was basically represented in the expressive ten-seconds-solo-voice and associated to the belly dance-inspired body movements.

When comparing other songs from Laundry Service which were directly published in English and Spanish (“Whenever, Wherever” and “Objection”), the differences in the voice are less obvious than in “Ojos así” / “Eyes Like Yours”, though intense frequencies around 3,000 Hz and noisy [s] consonants are more frequent in the Spanish versions. That means that the timbre and intensity of Shakira’s voice often differ in English and Spanish. What can be visualised with the help of spectrograms is also described by Kogan with regard to Laundry Service when he states that “songs that get both English and Spanish versions sound very different in the different languages” (Kogan 2001). And he explains more precisely:

[I]f you go back and check her Spanish-language LPs, they’ll confirm the difference. Her voice in English has a twisty trebly twang that’s appealing but doesn’t correspond to any accent I’ve ever heard […]. Shakira pronounces both syllables in “dear.” (“DEE-ear.”) She probably gets a kick out of singing like that. She recorded an album in English not to enter a multimillion-dollar market but to have the opportunity to make funny sounds with her voice. In Spanish she sings deeper and rounder, and she sounds more normal. Where there’s a direct comparison I prefer the Spanish versions, but I’m glad to have both. (Kogan 2001)

In contrast to Lechner or Berry, Kogan appraises Shakira’s experiments with her voice and describes the particularities of the vocal performance. More importantly, he appreciates the Spanish as well as the English recordings though the latter do not withstand direct comparisons. Perhaps, Laundry Service would also have benefitted from the insertion of a Spanish version of “Ojos así”, but only a Japanese edition (2002) included it as an additional track number 14.

Further Translation Strategies in Subsequent Albums

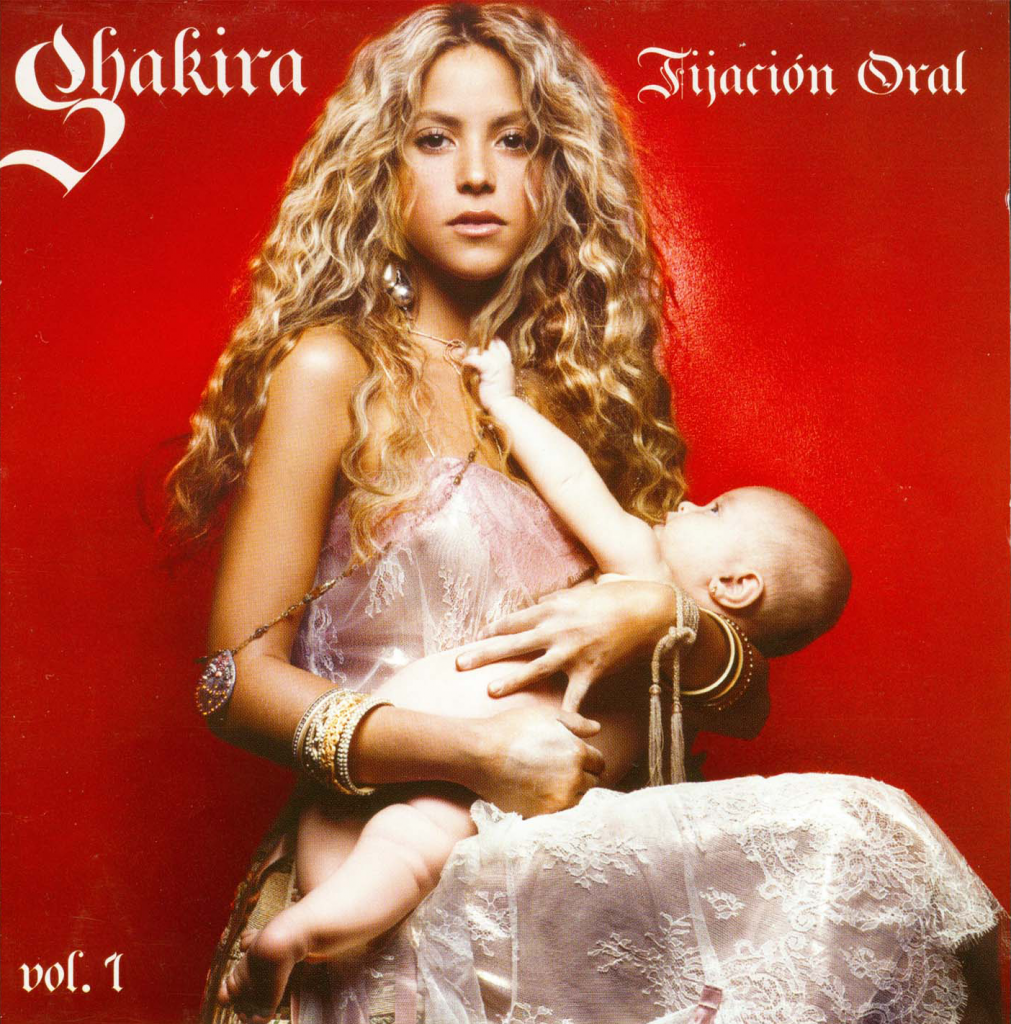

Kogan’s doubt about the aim of Shakira’s crossover seems ironic but drives attention to the challenge, the opportunities, the fun, and the risks of singing in different languages. Adapting to a new style for a new market may result in a loss of former fans. Reflecting on this in 2001, Shakira was quoted by Leila Cobo in Billboard as saying, “My Latin market is as important, or more [so], than others. It’s not that I’m abandoning one territory for the other. On the contrary: I’m expanding” (Cobo 2001, 5). It is remarkable that Shakira continually endeavored to fulfill the expectations of the different audiences in several languages. With Fijación Oral, Vol. 1 she released an album with songs in Spanish which was followed by Oral Fixation, Vol. 2 almost exclusively in English.

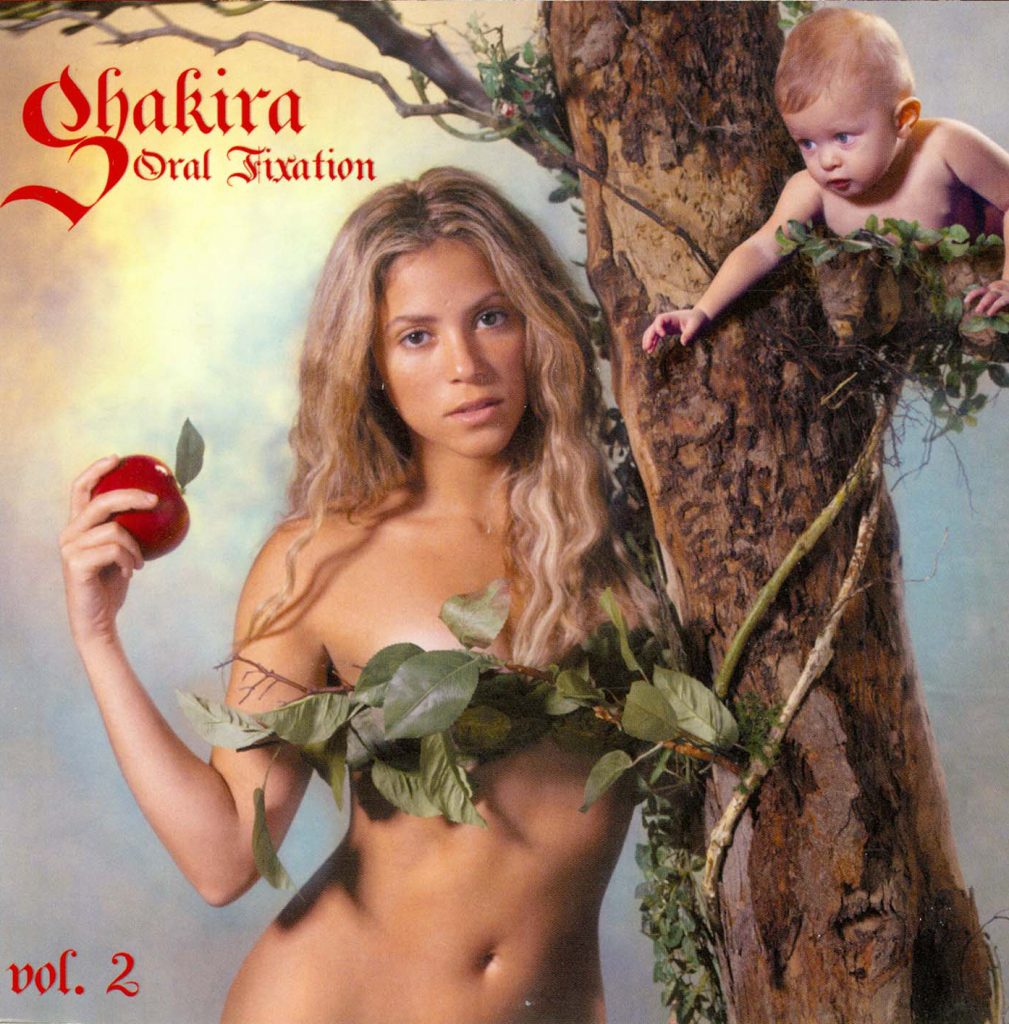

Fig. 8: Cover of “Fijación Oral, Vol. 1” (Sony Music Entertainment 2005, cover concept: Shakira, packaging concept and art direction: AR Media y Maria Paula Marulanda, photographer: Mario Sorrenti)

Fig. 9: Cover of “Oral Fixation, Vol. 2” (Sony Music Entertainment 2005, art direction and design: Shakira and Maria Paula Marulanda, photographer: Jaume Laiguana)

Besides the related titles, both covers show Shakira and a child representing feminine archetypes: On the Spanish cover, Shakira “holds a child in the same position as numerous ‘virgin and child’ paintings,” while on the English “she is an almost naked Eve, with a red apple in her hand and the same baby watching her but from a position in the tree as if Cupid or Eros could be here” (Gontovnik 2010, 148). At first glance, titles and covers attempt to assume the English album was a simple translation of the Spanish, designed differently in order to serve other gender ideologies in the English market, but the assumption fails. Oral Fixation, Vol. 2 also differs both musically and in concept as there is only one translated song. Track 1 “En tus pupilas” in Fijación Oral, Vol. 1 corresponds to track 11 “Something” in Vol. 2. The vocal expression is very similar in both versions of the song. The pronunciation in English is almost as clear as in Spanish with notable consonants such as the [s] at the beginning of the chorus (“something” respectively “siento”), and the sustained tones often develop into an irregular vibrato and show a rich overtone spectrum up to 4,000 Hz. Interestingly, the other track present in both volumes is the Spanish hit “La Tortura” which has not been translated into English but was arranged in three different versions (two of them on the Spanish album and another one on the English). Fijación Oral, Vol. 1 / Oral Fixation, Vol. 2 are probably the best examples of Shakira’s expansion and her strategy of serving different language areas with totally different songs.

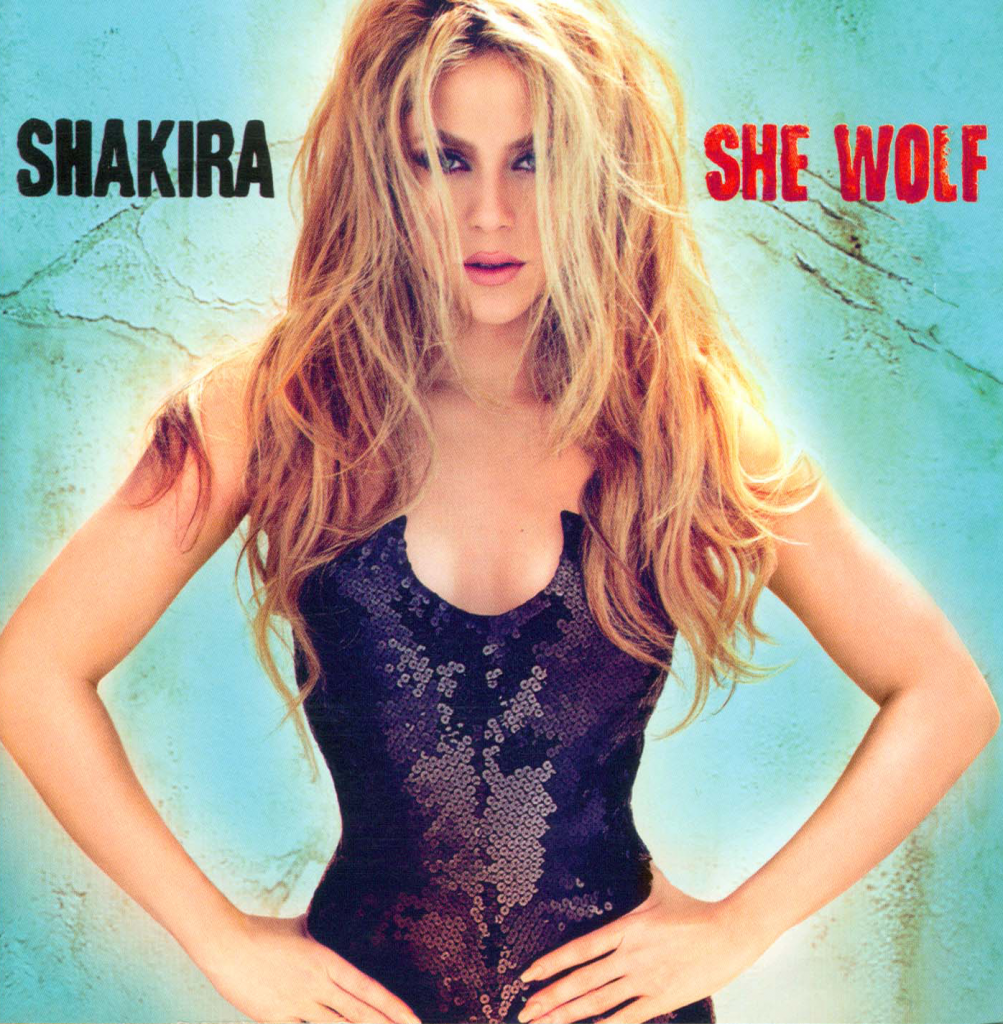

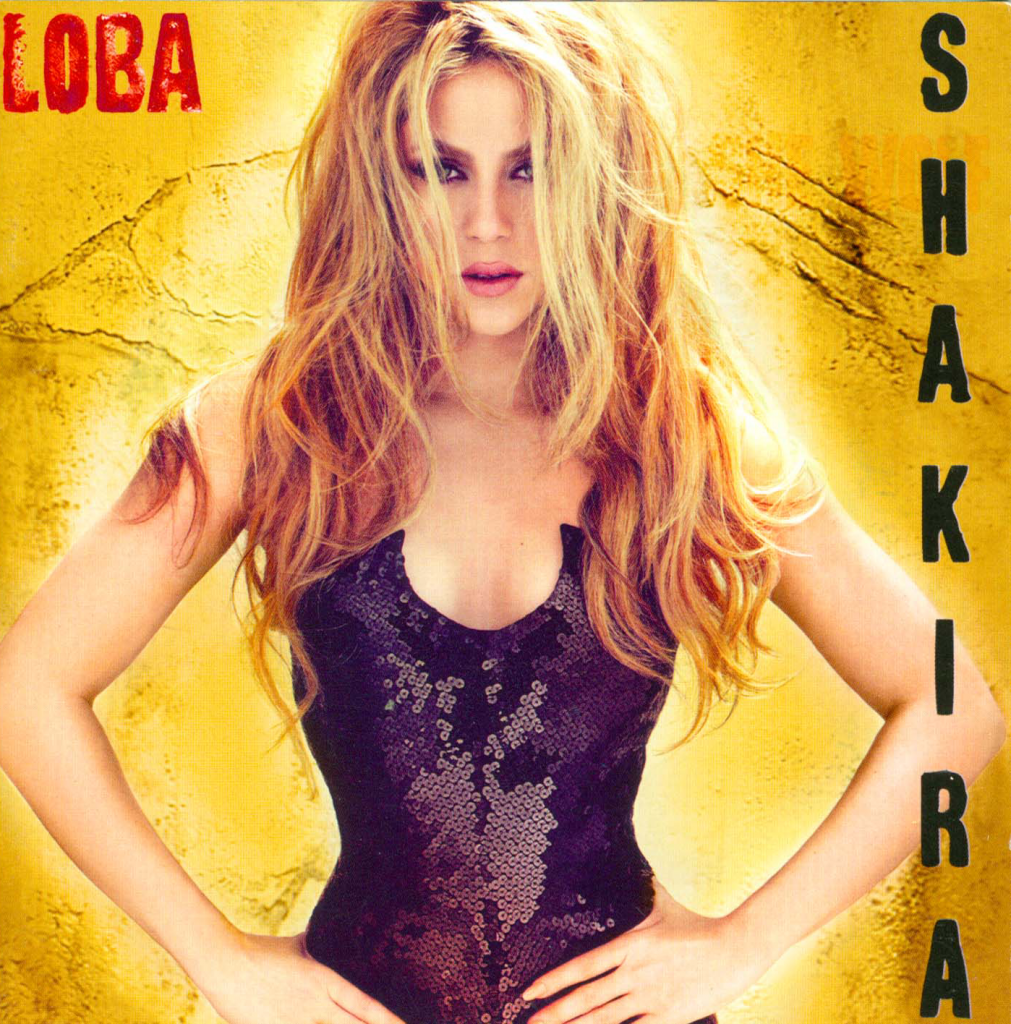

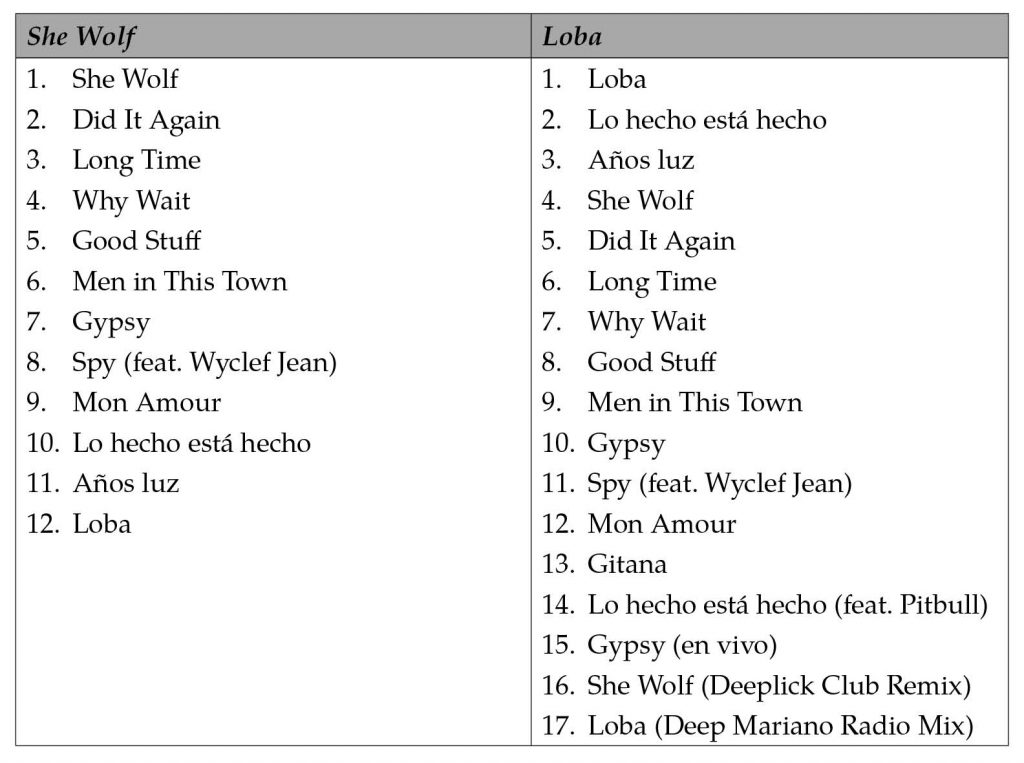

In contrast, the album She Wolf has a comparable Spanish version called Loba. The Spanish cover design is graphically identical to the English one and simply colored differently (Fig. 10–11). Certainly, the Spanish album, published in Argentina, contains more translated songs and in a different order: She Wolf finishes with “Lo hecho está hecho,” “Años luz,” and “Loba” as tracks 10 to 12, which are the Spanish versions of the English tracks 1, 2, and 4 and put at the beginning of Loba. Loba’s tracks 4 to 12 are identical with the tracks 1 to 9 of She Wolf, but Loba continues with an extra Spanish version of “Gypsy” (“Gitana”) and four other tracks in live or remix versions of “Lo hecho está hecho,” “Gypsy,” “She Wolf,” and “Loba.” As in the versions of “En tus pupilas” / “Something,” the vocal expression no longer shows such remarkable differences as found in “Ojos así” / “Eyes Like Yours.”

Fig. 10 & 11: Cover of “She Wolf” and “Loba” (Sony Music Entertainment 2009, art direction and design: Jaume Laiguana and Shakira, additional art direction and design: Christina Rodriguez, photographers: Mert Alas and Marcus Piggot)

The following album Sale el sol (2010) is again mainly in Spanish. Shakira (2014) is in English and contains the song “Can’t remember to forget you” / “Nunca me acuerdo de olvidarte” as the only translation. Depending on the countries, the track order on the albums and the bonus tracks differ as they did on Laundry Service and She Wolf. Counting all those examples, there are only a few songs that were produced in two or more versions altogether. Shakira’s oeuvre seems to serve both languages with different songs and subjects. While most of her Spanish songs are still written by herself or in collaboration with somebody, some English songs such as “Islands,” “Empire,” “You Don’t Care About Me,” “Cut Me Deep,” or “Chasing Shadows” on Sale el sol and Shakira have entirely been written by other authors.

Probably more than other Latin/o American stars before her and during her time, Shakira succeeded with her multiple-track approach to the international, English-dominated pop scene without leaving the Latin American market behind. Additionally, Shakira expanded further into transnationalism and multilingualism by mixing language and instruments into her performances. The Oral Fixation albums and the corresponding tour also represent a step to further multilingualism in Shakira’s oeuvre: “En tus pupilas” / “Something” included French lyrics and “Hips Don’t Lie”was bilingual (Spanish/English). In the case of “Hips Don’t Lie,” Roberto Agostini argues that the Latin/o song interpreted in English and performed together with the Haitian rapper Wyclef Jean turned out to be more successful even in the Spanish-speaking world than its monolingual version “Será, será (Las caderas no mienten)” (Agostini 2008, 213–14). According to Celis, Spanish phrases such as “bonita,” “mi casa,” “en Barranquilla se baila así” in the English version of “Hips Don’t Lie” have the function of pointing to Shakira’s Caribbean background and “the diffusion of Spanish” (Celis 2012, 205) since 1999. Such word plays and references in multilingual texts clearly get lost in translation and can only be compensated by radical rewriting (Eco 2003, 74). Since the English parts of “Hips Don’t Lie” were only translated into Spanish but “Será, será (Las caderas no mienten)” was not entirely rewritten, the translation only loses and the losses are not compensated.

Regarding multilingualism and the mix of different musical styles, the intro of the “Oral Fixation Tour” with guitarist Ben Peeler playing the Chinese zither guzheng and Shakira singing the song “Aatini al nay” (made famous by Lebanese singer Fairuz) in Arabic are emblematic. The Live from Paris recording shows that Shakira has explicitly placed herself in the tradition of song translation next to famous forerunners when performing Francis Cabrel’s song “Je l’aime à mourir” which he recorded in Spanish as “La quiero a morir” in 1979/80. Shakira surprised the audience with the French lyrics after the first verses in Spanish. Consequently, in 2014, she included the Catalan “Boig per tu” on the album Shakira, and, in 2016, Spanish, English, and French intermingled more prominently in the songs on the album El Dorado.

Conclusion

Shakira started translating her songs in the context of the “Miamization” of Latin American pop and its crossover boom in 1999. She developed a differentiated approach to language in the course of time, which can be witnessed in her albums until 2016. To get to the bottom of this process, comparisons of versions and detailed analyses of recorded tracks are a helpful tool. On the one hand, the microanalyses of “Ojos así” / “Eyes Like Yours” confirm musical aspects that some reviewers felt and described when Laundry Service was released in 2001. On the other hand, parameters of the vocal expression can be described more accurately with the visualization in spectrograms. Elements of vocal intensity such as the long irregular vibratos, particularly accentuated consonants, and a certain range of highlighted frequencies were lost when translating “Ojos así” to “Eyes Like Yours,” while visual aspects served as compensation: the play with feminine role models, dance sequences, and complex stage performances.

Nadia Celis argued that Shakira’s “emphasis on expressing herself through her body can be interpreted as a strategic shift aimed at communicating with a public that she could not address in her native tongue” (Celis 2012, 201). Consequently, the bodily performance belonged to the translation as a negotiation process at the time. Although Shakira has kept her blonde image and figure-accentuating dance performances to date, her vocal expression since Fijación Oral, Vol. 1 shows that she has also composed and acted more carefully in various languages and remained versatile as a musician. However, if we take Ernesto Lechner’s review of Laundry Service and the mention of “the Glen Ballard-penned ballad ‘The One’” (Lechner 2001, 126) into account, we can see that Shakira’s voice had already worked with English lyrics on Laundry Service as intense vibrato sequences with a rich overtone spectrum and the characteristic timbre in ballads such as “The One” or “Underneath Your Clothes” display: Perhaps the expressiveness of Shakira’s voice was changed, but not entirely lost when crossing over to the mainstream market.

The success of Laundry Service proves that in spite of certain losses in the translation process which were noticed by reviewers, the product Shakira worked as a whole in the new Anglophone market supported by new images and body concepts. Besides the outward appearance, multilingualism, translation, and transnationalism remain an integral element of Shakira’s recordings and stage productions which deserve further detailed analyses on the basis of the recorded sounds.

On the Author

Christina Richter-Ibáñez is a researcher and lecturer at the Institute for Musicology at the University of Tübingen, funded by the Margarete von Wrangell Postdoc Program. Her current research project studies the translation of songs and song lyrics in different cultural contexts. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Music and Theatre in Stuttgart with the thesis Mauricio Kagels Buenos Aires (1946–1957). Kulturpolitik – Künstlernetzwerk – Kompositionen (published in 2014).

I am grateful to Daniel Party for advice on the Latin/o music boom, to Elke Steinhauser for help with transcriptions and figures, and to Elizabeth Lee Hepach for advice on language issues. The spectrogram analyses were made with Sonic Visualiser 3.3 (Cannam, Landone, and Sandler 2010).

Annotation

[1] Research project “Songs in Translation: Übersetzungen von an Sprache gebundener Musik. Kulturelle Kontexte und digitale Analyse,” University of Tübingen, April 2018–March 2023, Link.

Discography

Marc Anthony. 1999. Marc Anthony. Sony Music Entertainment Inc. Columbia 4949372000.

Ricky Martin. 1999. Ricky Martin. Sony Music Entertainment Inc. Columbia 4944062000.

Shakira. 1997 [1995]. Piez descalzos. Sony Music Entertainment (Colombia). Columbia 4852752.

Shakira. 1999 [1998]. Dónde están los ladrones? Sony Music Entertainment (Colombia). Epic 4857196.

Shakira. 2000. MTV unplugged. Sony Music Entertainment (Colombia) / MTV Networks Latin America. Epic 4975962000.

Shakira. 2001. Laundry Service. Sony Music Entertainment (Holland). Epic 4987202021.

Shakira. 2001. Servicio de lavandería. Sony Music Entertainment (Holland). Epic 4987209000.

Shakira. 2005. Fijación Oral vol. 1. Sony BMG Music Entertainment. Epic 5201622000.

Shakira. 2005. Oral Fixation vol. 2. Sony BMG Music Entertainment. Epic 82876815852.

Shakira. 2009. She Wolf. Sony Music Entertainment. Epic 88697381882.

Shakira. 2009. Loba. Sony Music Entertainment (Argentina). Epic 886976753528.

Shakira. 2010. Sale el sol. Sony Music Entertainment (Holland). Epic 88697797862.

Shakira. 2011. Live from Paris. Sony Music Entertainment US Latin LLC. 88697999072-1.

Shakira. 2014. Deluxe edition. Ace Entertainment / Sony Music Entertainment. RCA 88843049552.

Shakira. 2016. El Dorado. Sony Music Entertainment US Latin LLC. 88985444582.

Filmography

Shakira. 2002. MTV unplugged. Sony Music Entertainment (Holland) / MTV Networks Latin America. 2015929000.

Shakira. 2007. Oral Fixation Tour. Sony BMG Music Entertainment. 88697204939.

Shakira. 2008. Live & off the Record. Sony BMG Music Entertainment. 88697373439.

Shakira. 2011. Live from Paris. Sony Music Entertainment US Latin LLC. 88697999072-2.

List of References

Agostini, Roberto. 2008. “Shakira dembow. Fare dischi pop, di successo.” In Il nuovo in musica. Estetiche tecnologie linguaggi, edited by Rossana Dalmonte and Francesco Spampinato, 213–22. Lucca: Libreria Musicale Italiana.

Cannam, Chris, Christian Landone, and Mark Sandler. 2010. “Sonic Visualiser: An Open Source Application for Viewing, Analysing, and Annotating Music Audio Files.” In MM ‘10 Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Multimedia: 1467–68. Accessed July 19, 2020. ⁄ Link.

Celis, Nadia. 2012. “The Rhetoric of Hips. Shakira’s Embodiment and the Quest for Caribbean Identity.” In Archipelagos of Sound: Transnational Caribbeanities, Women and Music, edited by Ifeona Fulani, 191–216. Kingston: University of West Indies Press.

Cepeda, María Elena. 2000. “Mucho loco for Ricky Martin; Or the Politics of Chronology, Crossover, and Language Within the Latin(o) Music ‘Boom’.” Popular Music and Society 24 (3): 55–71.

Cepeda, María Elena. 2001. “Columbus Effect(s): Chronology and Crossover in the Latin(o) Music Boom.” Discourse 23 (1): 63–81.

Cepeda, María Elena. 2010. Musical ImagiNation: U.S.-Colombian Identity and the Latin Music Boom. New York: NYU Press.

Cobo, Leila. 2001. “Finding More Latin Music Fans.” Billboard 113 (45), November 10: 5–6.

Diego, Ximena. 2001. Shakira. Mujer llena de gracia. La historia detrás de la sensación latinoamericana ganadora el Grammy. Biografía no autorizada. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Eco, Umberto. 2003. Mouse or Rat? Translation as Negotiation. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Fiol-Matta, Licia. 2002. “Pop Latinidad: Puerto Ricans in the Latin Explosion, 1999.” Centro Journal 14 (1): 27–51.

Fuchs, Cynthia. 2007. “‘There’s My Territory’: Shakira Crossing Over.” In From Bananas to Buttocks: The Latina Body in Popular Film and Culture, edited by Myra Mendible, 167–81. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Gontovnik, Mónica. 2010. “Tracking Transnational Shakira on Her Way to Conquer the World / Rastreando a la Shakira transnacional en su cambio a la globalización.” Zona próxima 13: 143–56. Link.

Kogan, Frank. 2001. “River Deep, Freckle High.” Village Voice, December 25. Accessed July 19, 2020. Link.

Lechner, Ernesto. 2001. “Latin Rock Superstar Gets Lost in Translation.” Rolling Stone 881, November 8: 126.

Marc, Isabelle. 2015. “Travelling Songs: On Popular Music Transfer and Translation.” Journal of the International Association for the Study of Popular Music 5 (2): 3–21. Accessed July 19, 2020. Link.

Mendez Berry, Elizabeth. 2001. “Shakira. Laundry Service. Sony.” Vibe 9 (12): 18.

Party, Daniel. 2008. “The Miamization of Latin-American Pop Music.” In Postnational Musical Identities: Cultural Production, Distribution and Consumption in a Globalized Scenario, edited by Ignacio Corona and Alejandro L. Madrid, 65–80. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Rohter, Larry. 2000. “Rock en Espanol Is Approaching Its Final Border.” New York Times, August 6. Accessed July 19, 2020. Link.

Proposal for Citation

Richter-Ibáñez, Christina. 2021. “When ‘Ojos así’ Became ‘Eyes Like Yours’: Translation as Negotiation of Lyrics, Sound, and Performance by Shakira.” In Pop – Power – Positions: Globale Beziehungen und populäre Musik, edited by Anja Brunner and Hannes Liechti (~Vibes – The IASPM D-A-CH Series 1). Berlin: IASPM D-A-CH. Online at www.vibes-theseries.org/richter-ibanez-shakira.

Cover Picture: Shakira’s album covers 2001, 2005, and 2009 (credits: see Fig. 2, 9, 11).

Abstract (Deutsch)

Die wissenschaftliche Forschung zu Shakira hat sich auf die Imagebildung und die transnationalen Performances der Sängerin seit dem Übergang vom lateinamerikanischen zum globalen Mainstream-Markt in den Jahren 1999 bis 2001 konzentriert. Im Gegensatz dazu widmet sich dieser Aufsatz dem Klang ihrer Songs und zeigt, wie sich der vokale Ausdruck der Sängerin veränderte, als sie begann auf Englisch zu singen. Der damals zentrale Song “Ojos así”, dessen verschiedene Aufnahmen und vor allem die Übersetzung “Eyes Like Yours” sind Gegenstand der Analyse. Darüber hinaus zeigt ein Überblick über die Alben seit 2001, dass die Sängerin den spanisch- und englischsprachigen Markt mit unterschiedlichen (vokalen) Performances bedient und Mehrsprachigkeit sowie Übersetzung wichtige Elemente ihrer künstlerischen Produktion sind.