While record collecting is an often acknowledged practice within popular music that is mainly attributed to male collectors, research on actual collections is rare. This article presents a forensic cultural studies research based on the record collection of a female collector who was a classically trained musician and LGBTQ+ activist in the 1970s and 1980s USA. Starting from the materiality of the collection, traces of gender, feminism and lesbian culture are revealed and connected with the collector´s biography. It becomes clear that through research on popular music archives alternative, marginalized popular music narratives become visible.

[Download PDF-Version] | [Abstract auf Deutsch]

Introduction

In between academic occupations, I worked part-time in a second-hand record store specialized in popular music from the 1950s until today. When I had a chance to look at collections that were bought by the shop owners from heirs, I realized that such collections contain substantial information about the collector’s personal relationship, interest and perspective towards music. I considered it may be valuable for a historical perspective towards what people do with popular music and what effect it might have to reveal such stories. Yet in a commercial store there is no time for such endeavors. A collection comes in and is immediately torn apart, divided into commercial categories: easy to sell, special gems with high price, low price etc. and sold record by record.

By coincidence, some time before an heir had asked me for help with a record collection, and now I agreed to do this. I had no idea where it would lead me to. Here, too, were many trivialities at work. The vinyl record collection is part of the heritage of a classically trained female musician, an oboist. When she died she bequeathed all music-related objects to another baroque oboist, a good friend of hers. The heir kept the instruments, sheet music and CDs. He passed the vinyl record collection on because it contained hardly any material corresponding to his personal research interests. The collection consists of around 863 records, 543 with classical music and 320 with popular music. With this distinction I follow the collectors practice: she stored classical and popular music records separately. What such practices tell us about understandings of music will be the main question of this article. The heir supported the idea of making the collection accessible for research. I arranged for the classical records to be given to the Institute for Music Research, Berlin, and I am dealing with the popular music part in the following. Research on the classical records is currently in progress in collaboration with the Institute for Music Research. I can disclose the identity of the collector upon request. For this article I have decided to anonymize the identity.

Biographical Information

The collector was born in Chicago in 1947 and died in El Cerrito, in California, in 2016. She grew up in Chicago and then moved to San Francisco. Later, in the 1990s she moved to the Netherlands. She was economically secure through an inheritance. She devoted her life to music – and to activism. In the 1970s and 1980s she was part of the LGBT* community in California. She rode motorcycles and took part in the San Francisco Gay Pride Parades. She trained oboe, she repaired oboes and collected music. In the late 1980s she moved to Europe and started to study baroque oboe. She first studied at the Hilversum Conservatorium (later merged with the Conservatorium van Amsterdam), then settled in Amsterdam. Later she took private lessons with several teachers.

All biographical information comes from two interviews with the heir and a nephew. The collector hardly had any contact to the rest of the family because they did not accept her sexual orientation. Both sources have little information about the life of the collector in the 1970s and 1980s but they make two central claims: the collector persued an activist lifestyle and rock music was very important for her during this time.

Aim and Scope of this Article

This article presents exploratory research. In classical studies of cultural studies, questions are asked about how people deal with things culturally. Here, the approach is to look for traces of this interaction in the materiality of a record collection and to set out in search of the cultural fields in which this interaction once took place – a forensic cultural studies approach one might say. Its theoretical implications about the relationship of humans and material objects as is recently being discussed around the term new materialism (Gamble et al 2019) are not being dealt with here. Instead I take an experimental approach to what can be analyzed when empirical and ethnographic access to acting out such relations is not possible anymore.

The collection serves as a starting point and reference from which questions lead in various directions. The article presents a few major themes found in the collection: gender and feminism, female musicians in popular music and the genre of women´s music. By following such strands, I try a tentative answer to a question posed by Martin Pfleiderer regarding private popular music archives: „How can music archives contribute as a corrective to the general wikipedification and canonization of popular culture?“ (Martin Pfleiderer 2011, 12, translation by the author).

Canonization can be seen as an inevitable and very useful process. Carys Wyn Jones (2008) has shown its social and aesthetic dynamics for rock music. Furthermore she highlights the instability and growing diversity of canons, making them “a battleground for representation in history” (p. 7). In this article a private record collection makes exclusions on this battleground visible.

Disclosure

Taking a specific position towards a field of research always results in certain advantages and disadvantages. As a starting point the researcher’s own position should be disclosed to make it accessible and fruitful for the research process. I am a musicologist (white, male, German) with a focus on popular music studies. Furthermore, I am a record buyer since 1982. I am accumulating vinyl records for diverse reasons, which are shifting over time: listening at home to artists and styles I like, DJing (mainly in the 1990s and 2000s), and my musicological profession. I am straight and besides a few friends I have no personal connection to the LGBTQ+ communities and their concerns that come upfront in this article.

Researching Record Collections

There are countless private music collections. But why are certain acquired objects kept and others not? When does accumulation become collecting? For Roy Shuker (2010) a minimum requirement is choosing records on the basis of certain criteria and developing social practices like visiting record stores. He defines record collecting as a set of social practices: He asks who collects what and why, and what is the process of collecting, including places of acquisition, the pleasure of hunting and finding. He conducts interviews with collectors and finds numerous collecting strategies, for instance: collecting formats, genres, performers, record labels, producers and combinations thereof. Collecting is a highly gendered activity, and collections and collector traits that fit the masculine stereotype receive the greatest social rewards. But who collects records? Male collectors form the major part of Shuker’s sample; 56 versus 11 females.

Empirical studies on record collecting like Shuker’s are rare but there is a large body of popular magazines and books dedicated to record collecting. Here, too, male collectors are by far the most present. For instance, the coffee table book Dust & Grooves: Adventures in Record Collecting (Eilon Paz 2015) features photographs of collectors and their collections. Here the gender ratio is similar to Shuker’s sample: 117 male, twenty-one female and maybe one diverse. We do not know whether such a 5 to 1 ratio is coincidental, due to the sampling strategy or social norms that render female collectors more invisible. As Straw (1997) points out, male collectors are constructed as the social norm of record collecting with personality traits like hipness, connoisseurship, bohemianism, and the adventurous hunter. A recent study with a small sample of vinyl record collectors across all genres in Stuttgart indicates that the essential difference in the collecting behaviour of men and women lies in the motivation to buy and collect records (Fischer et al 2017). For female record collectors today, the music, the atmosphere and also socio-cultural aspects are in the foreground. These are just as important to men, but in addition, for them prestige, achievement and competition with other collectors are important. They show off their achievements in the collector scene whereas women collect more in privacy. This hints at potentially bigger invisibility of female collectors yet the authors also state that they found fewer female collectors than men. For the authors the reasons are manifold: a smaller set of motivations for collecting but also patriarchal elements in the broader society. Women generally spend a third less time on leisure activities and are generally less involved in music and less prominent in the music industry. Furthermore, music history is usually told as “his story”, not “her story”, by men emphazising stories of men. As a result women become even more invisible (Kreutziger and Losleben 2009). To sum up, it can be assumed that today fewer women collect records than men, and male collectors still get by far the main public interest, rendering female collectors nearly invisible.

In general, collecting music can be seen as a focal point for attributions to technology, associations with materiality, economic and aesthetic values (Christian Elster 2021). “Collecting music always has something to do with the self-image and self-positioning of the collecting individuals. As carriers of multilayered subjective and collective meanings, the collected things and data form an interface between individuals and their social environments.” (Elster 2021: 10, translated by the author) The forensic cultural studies analysis presented here tries to reconstruct collection strategies and to uncover traces of those links. If we add the notion of time passing while collecting, an individual collection might also become an archive with biographical connotations, showing shifts in self-image and represented meanings.

Research Approach

Research on record collections is rather rare. There is no methodology present so far. Authors like Shuker focus on the collectors, not their collections. So I chose a heuristic approach. Through the whole process of working with the collection I keep filling a memo with anything that strikes me, form hypotheses and pose questions. To gain as much information from the materiality of the collection as possible, a protocol of the state of the records since handover was made. With this information I try to recreate the original sorting of the collection. I then catalogue the collection using the Discogs database. Discogs.com is the biggest online database and marketplace for vinyl, CDs and cassettes on the internet. The entries concerning record releases are made by the users, mainly collectors and merchants. Most records in the collection are already present on Discogs as data sets. The whole data set can later be exported as a csv file for further analysis. Upon entry into the database, I form heuristic categories and log conditions of record and sleeve. I note special features (notes, stamps, stickers, etc.). While cataloguing I listen to each record, and listen through most of them. Parallel to this, I collect context information concerning the collection. I do internet research on records, musicians and record shops and do interviews with friends, colleagues and family to gain biographical information about the collector and her social environment. So far I have conducted three interviews: with the heir, a younger relative and a musician colleague.

Unboxing

The records were packed in boxes by a moving company in Amsterdam. But the old order in the collector’s shelf is partly still recognizable, in blocks of 10 to about 30 records. This corresponds to the number of records that can be grasped en block when taken from a shelf. In the pop section, male musicians and female musicians are separated, each alphabetically from Z to A as seen from the front cover. When placed on a shelf and seen from the side this resembles A to Z from left to right. A small block contains women composers (classical). In other recognizable blocks are jazz records and blues records, as well as ethnographic records with recordings from various regions of the world. Those are not separated by gender. The records are mostly in very good condition, and some are still sealed in their original shrink wrap.

Strands becoming visible

The popular music records were standing close together on the shelf. This is indicated by edgewear at the corners and ringwear at the highlighted areas. They are segregated by gender: male and female. The order was in both cases alphabetical A to Z from left to right. The records have been carefully handled. There are hardly any scratches on the records, and there are traces of damp cleaning. The majority of the records were probably purchased new. Are there any used ones among them?

Most of the records with price tags were purchased at three stores in San Francisco: Streetlight Records, Down Home Music and Butch Wax. The latter was a small store for the LGBTQ community while Streetlight Records has several branches and still exists today. I tracked down the former manager from the 1980s and sent him photos of the price tags. He said that new records were always priced with the digit 8 at the end and used records with 5 or 0. Records with both kinds of price tags are in the collection; most of them were bought new.

There is a biographical component to the collection. There are records from the teenage days to the late 1980s with changing emphasis on different artists. In the late 1980s, the collector switched to CDs for further collecting. Yet she took the nearly 900 records and the turntable with her when she moved to Europe, at the same time as she switched to CD. This indicates that the collection was very important to the collector.

In numbers, within the pop part of the collection, 54% (108 records) are male musicians and 46% (91) are female. This is a very high percentage of female musicians. The ratio is almost balanced, and that is remarkable in that many more male artists are successful in pop than females. For instance, if you look at the Billboard Top 100 in the U.S. from 2003 to 2016, among the 30 best-selling hit singles, they feature 70% male and 30% female artists (Sánchez-Olmos et al. 2021). In my personal collection there is an even bigger bias towards music by male artists. Studies about gender balance in record collections do not exist. In general, male artists are much more present on the music market and so, one might guess tend to be more prominent in music collections. Here it is different. We find a balanced gender proportion that is physically visible on the record shelf. This is highly remarkable. The social demand of gender equality has become a physical reality in a collection of cultural objects. In the following I will take a look at two focal points from the male and the female part of the record shelf as examples that show this gender aspect, too: The Beatles and women’s music.

Fandom and Materiality

In the pop collection, about two thirds of male and female artists alike are present with just one record (male artists 70.4 %, female artists 66.7 %). In female pop, the biggest numbers of records per artist are Joan Armatrading with six and Cleo Layne with five records. There are no artists with 4 and five artists with 3 records.

Artists with the most records in the collection (earliest pressing)

| Female artists | Number of records | Record information | Year span of pressings |

| Cleo Laine | 5 | 2 records still sealed. | 1973 – 1981 |

| Meg Christian | 3 | All original pressings from the women-led label Olivia Records. | 1974 – 1981 |

| Joan Armatrading | 6 (one doublet) | All first release pressings. Doublet still sealed. | 1975 – 1981 |

| Terry Garthwaite | 3 (plus one record of her duo “San Francisco Ltd.” From 1974) | 1975 – 1984 | |

| Holly Near | 3 (plus one duet album with Jeff Langley) | All records are released on Holly Nears own independent label Redwood Records and original pressings. | 1976 – 1982 |

| Sweet Honey In The Rock | 3 | All albums still originally sealed and original pressings on small labels. | 1976 – 1981 |

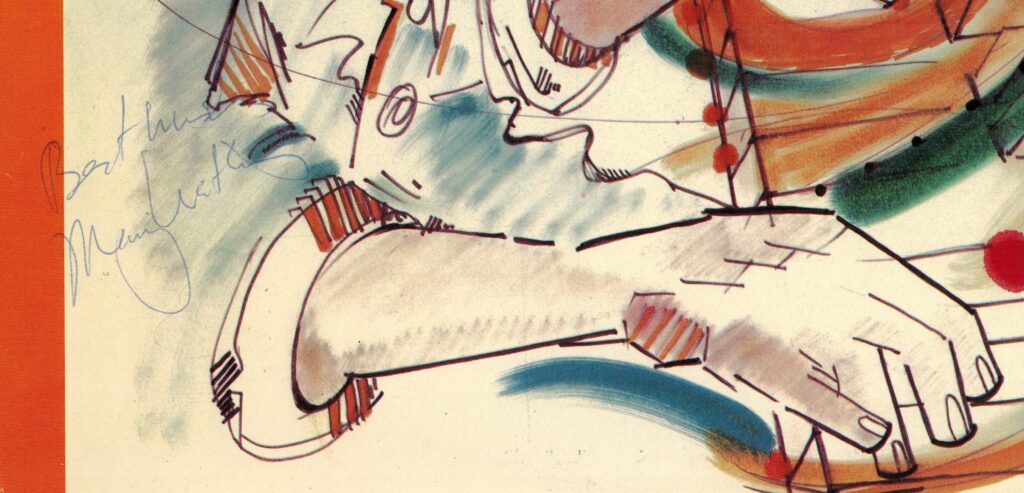

| Mary Watkins | 3 | All original pressings on small labels, one on Redwood Records. One record with inscription “Best Wishes Mary Watkins” | 1978 – 1985 |

Among male artists the biggest numbers are The Beatles (12 records), Steely Dan with nine and David Bowie with eight records. If you count two solo albums by Donald Fagen in, the number for Steely Dan becomes even closer to The Beatles. Among female and male artists alike there are just a few artists with a high number of records. Why are the numbers smaller with female artists? Do those artists publish fewer records? Cleo Lane and Joan Armatrading both published a high number of records at a regular frequency. Other female artists in the collection published far less. For instance, the all-women jazz combo Sweat Honey In Rock published only three records – all of them are in the collection.

Artists with the most records in the collection (in order of appearance in collection)

| Male artists | Number of records | Record information | Year span of pressings |

| Jacques Brel | 6 | 4 import records from France. One US reissue pressing (1960). | 1960 – 1964 |

| Bob Dylan | 6 | All first release year US pressings | 1962 – 1965 |

| The Beatles | 12 (one doublet) | All first release year US pressings (except the doublet, a British pressing) | 1964 – 1968 |

| Cat Stevens | 6 (one doublet) | All first release pressings. Doublet record still sealed. | 1970 – 1974, 1980 |

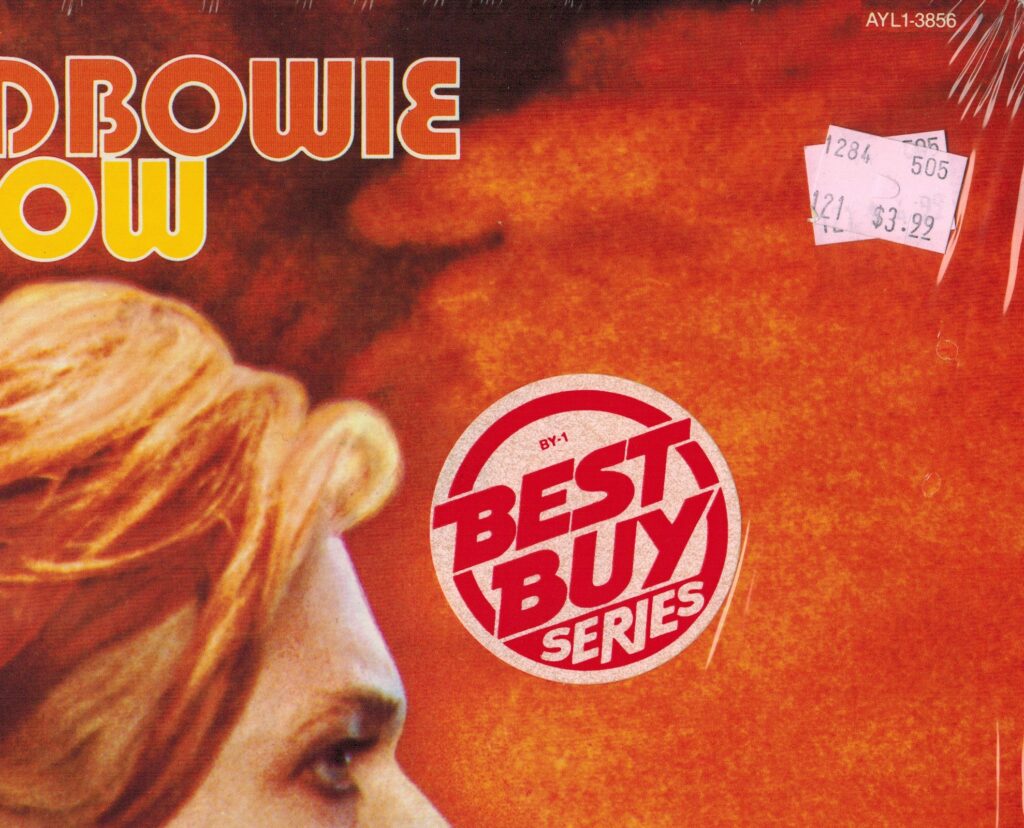

| David Bowie | 8 | 4 records are reissues and still sealed. | 1974 – 1987 |

| Steely Dan | 9 (two doublet) | All but one first release year US pressings | 1974 – 1984 |

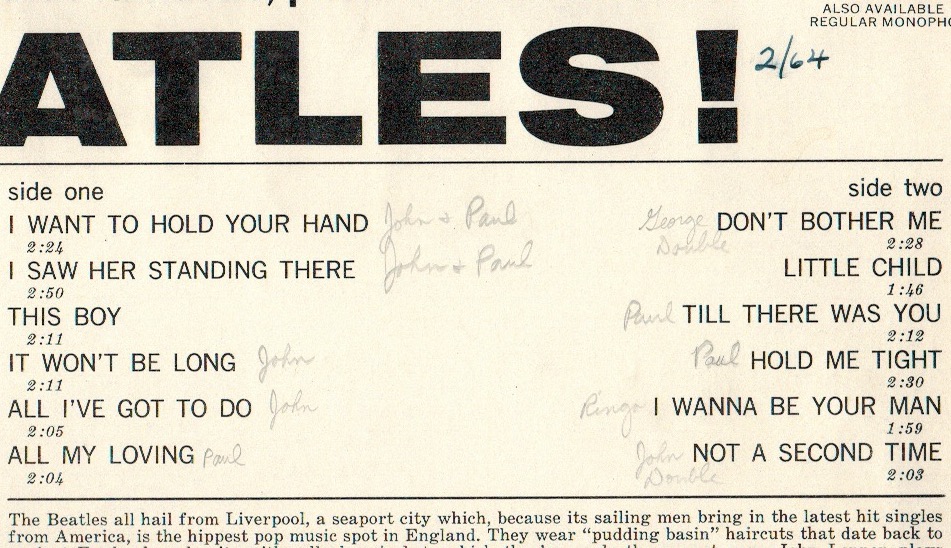

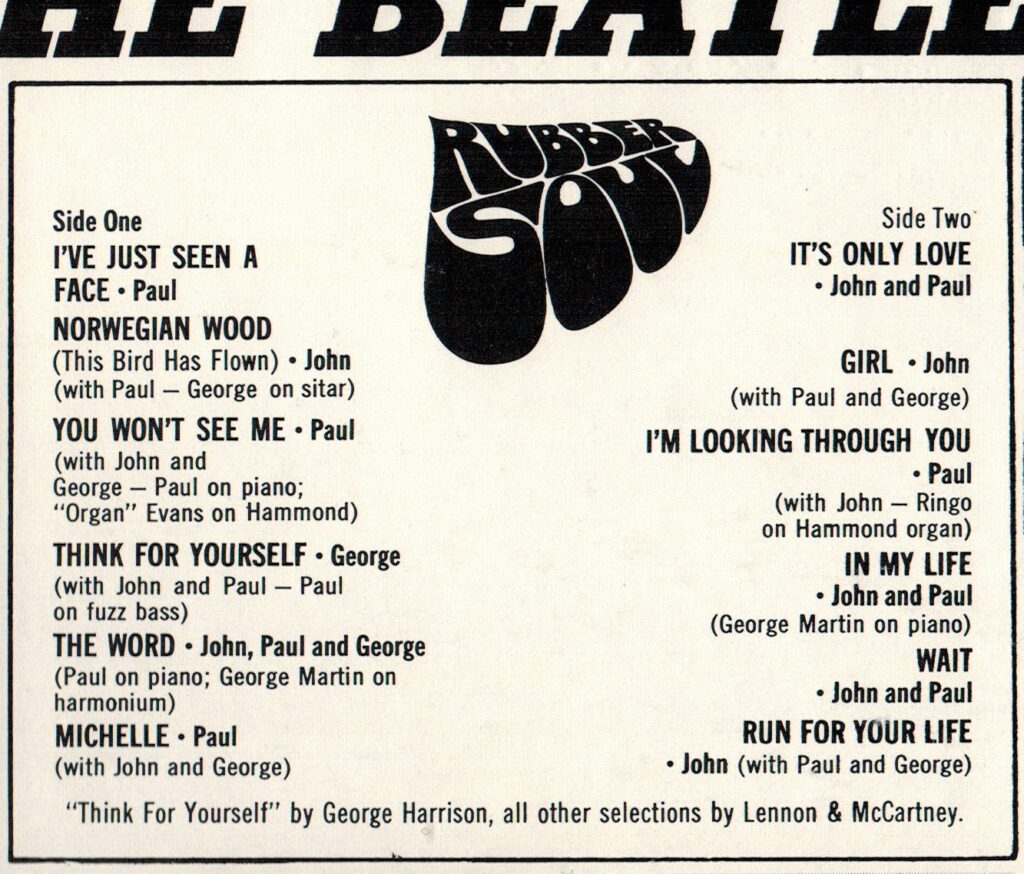

Concerning The Beatles, all records are first US pressings, except one doublet, a second copy of Rubber Soul which is a 1968 British pressing. The early pressings indicate that the collector bought all those records shortly after they were released. This might hint at a fan relationship, eagerly purchasing every new album as soon as it is available. Additionally, one of the early records shows traces of typical fan behavior. With a pencil the collector wrote the names of the Beatle(s) who sang next to the songs.

One year later, on the album Rubber Soul this information, once sought after and discussed by the fans, is already provided on the back cover of the album by default.

The earliest records in the collection are by Jacques Brel. They date from 1960 to 1964. Four of them are import records. Import records are expensive and hard to get. First pressings and import records might hint at bigger fandom.

In contrast to The Beatles, four of the eight David Bowie records are reissues and still sealed. They are unused. Those records were bought when the collector came across them for a budget price. They might have been collected for completeness rather than an urge to listen to the music. But what was the reason for collecting? We shall get to a hypothesis through looking at some of the female artists later on. For the moment we will stay with The Beatles.

The collector was a 17-year-old teenage girl when she bought her first The Beatles’ record in 1964. We do not know when she had her coming out. Anyway, being 17 in 1964 was a perfect age to be part of the Beatlemania fandom (Hertsgaard 1995). The accounts of female teenage fans getting crazy and screaming at The Beatles’ concerts in the USA from 1964 to 1966 are legion but they are rarely explained. The historiography of pop music mostly describes the amazement and incomprehension of the observers of the time. Maybe because this history is mainly written by men? In recent years female researchers revisit Beatlemania fandom. Nicolette Rohr states “the screams constituted a rebellion against the gendered norms of public behavior” (Rohr 2017: 1). For young women, Beatlemania fandom was a means to transgress gender norms. Instead of the supposed ladylike behavior the girls publicly displayed emotional frenzy. Sasha Geffen presents another telling interpretation in her recent book Glittering Up The Dark (2020). Sasha Geffen’s book is dedicated to the question of how pop music has broken down and subverted the binary understanding of gender since the 1950s. In her chapter on The Beatles, she writes that the bands’ early success can only be understood together with this fan phenomenon. The Beatles were the first boy band. Not only did they offer four different boys to relate to, but these boys showed a new image of masculinity. They were not alpha males. They formed a team, as equals, and at most ironically mimicked alpha male’ games. Their hairstyles crossed the line of shirt collars. They were masculine, but unwilling to submit to the discipline imposed on men.

In the lyrics of the early The Beatles songs, they adopt a rather passive attitude usually attributed to women. „I want to hold your hand“, „I saw her standing there“ „I wanna be your man“ „Please please me“. Furthermore, The Beatles covered many songs that were originally published by black American girl groups (Geffen 2020: 21). Take for instance “Please Mr. Postman”, originally sung by The Marvelettes in 1961. In the collection it is on the album The Beatles‘ Second Album from 1964. The Beatles adopt the girl groups’ typical polyphonic singing style, vocal delivery and the lyrical narrator’s passive position through exchanging female with male pronouns when necessary. “They´re boys emulating girls who have grown tired of gender scripts: boys trying to be girls who are sick of what it means to be a girl.” (Geffen 2020: 23)

In those songs The Beatles did gender-bending: they offered a different masculinity that was enhanced by supposedly female qualities. Furthermore, The Beatles‘ restraint opens up the space for the girls to play a more active role (even if only imagined for the time being). We do not know whether the collector might have been initiated to gender-bending through the Beatles but in light of the further development of the collection it seems reasonable to presume that she had a sensibility for the shifts in gender roles that The Beatles played out. Further biographical information is needed here but so far no companion from this time could be interviewed.

Women´s Music

Female pop musicians became relevant in the collection in the early 1970s when the collector was in her mid-twenties. Among the female artists with the most records quickly collected, a specific subgenre of popular music becomes prominent: women´s music. All female artists with three records in the collection belong to this genre (see table one). Women’s music is an established term for the music of the lesbian and feminist scene in the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. Many of the musicians were lesbians. The term originally meant “music by women, for woman, about women and financially controlled by women.” (Lont 1992: 242) Women musicians accounted to this scene were forming bands, record labels, and distributors. They were the first companies in the U.S. music market founded by women and were organized in part as collectives. The most famous example is the label Olivia Records. Production, design, management and distribution was entirely in the hands of women. They formed an alternative music industry that was widely ignored by the mainstream press and other subcultures.

All key albums and artists of this genre and some less successful releases are in the collection. Many albums are shrink-wrapped and unopened. On two San Francisco productions, the collector plays the oboe on one track each. Lont explains that for the lesbian scene, knowledge about women´s music artists marks belonging to the lesbian scene. The presence of these records in the collection indicates that the collector herself was likely part of this scene and that the records have a value as lesbian culture artefacts. It was a matter of belonging and respect to own those records. It is not necessary to listen to every album. It is more a matter of completeness. For instance, Cris Williamson´s album The Changer and The Changed (1975) was the biggest selling album of women´s music in the 1970s. In the collection it is contained in the Second Edition and still shrink-wrapped. From Sweet Honey In The Rock, a five piece all-women Jazz band, all three albums are in the collection, and they are still shrink-wrapped. Because of its completeness it can be said the women´s music is a special focus point in a collection that has a general strand of collecting music by women. The women´s music artists were stored among the female popular musicians A to Z order. This might be interpreted as another claim for equality: women´s music as an equal part of female popular music.

The collector plays the oboe on two of those records: Gayle Marie – Night Rainbow (1982), and Silvia Kohan – Finally Real (1984). The latter inspired the title of his paper because it can be read as a celebration of lesbian culture becoming real in the sense of thriving and flourishing in contrast to being hidden and suppressed in the past. The two albums are marginal within women´s music but they show that the collector knew women´s music musicians. Both albums were produced by Mary Watkins, an African-American musician and composer who was central to the scene. Many women´s music records were produced by her. Two more of those albums are in the collection: Linda Tillery – Linda Tillery (1977, co-production), and Debbie Saunders – A Shot In The Dark (1984). As a musician, Mary Watkins contributes to the following women´s music records in the collection: Teresa Trull – The Ways A Woman Can Be (1977), Meg Christian – Face The Music (1977), Meg Christian – Turning It Over (1981), Gayle Marie – Night Rainbow (1982), Linda Tillery – Secrets (1985). As arranger Mary Watkins is involved on Holly Near – Fire In The Rain (1981).

Mary Watkins‘ first three solo albums are in the collection, too. The second album Winds Of Change (1982) is one of two records in total in the collection that carry a handwritten inscription: „Best Wishes Mary Watkins“. I was therefore glad that she is still available today and contacted her to do an interview concerning the collector and women´s music in general. The interview was conducted via a video chat platform. Mary Watkins, born 1939, had asked for some of the interview questions in advance so she could better prepare. Concerning the collector, she says she knows her from the classical music scene in San Francisco. Mary Watkins approached her specifically in cases when she needed an oboe player. For the song “Taking My Baby Uptown” Mary Watkins arranged an instrumental part in baroque style, and she knew that the collector was specialized in this music. As far as Mary Watkins knows, the collector had no further personal connection to women´s music. The information shows that it is not sufficient to look at the popular music collection only. Her classical work and collection must be taken into account, too. More information is needed to verify Mary Watkins’ account. For now it seems it was through these activities and networks that the collector came in touch with women´s music protagonists.

In the literature women´s music reach is disputed. Sasha Geffen states that women´s music was produced only for a small, limited audience of feminist and lesbian women. In contrast, Synthia Lont points out that it aimed to reach as many women as possible. Mary Watkins also makes a strong point for the latter argument. “The music was a means to an end: empowering women.” For Mary Watkins, women´s music was very successful in doing so.

In a way, both points are adequate, and this position can be clarified by women´s music aesthetics and its mostly isolated place in the music business. Despite this separation the above mentioned album The Changer And The Changed is one of the best-selling independent records in the 1970s USA. Its production aesthetics clearly belong to the folk music genre. Most popular music subcultures develop a certain sound that makes its contributions immediately recognizable and signifies a distance to mainstream music. With women´s music it is different. Their artists draw from all genres popular at the time except rock music: Folk, Blues, Jazz, Soul, Funk. They play and sing with great skill. It is the female voice where aesthetic novelty happens: many women´s music artists sing in a deep alto register called the butch voice, “low and dark […] ragged and inflamed” (Geffen 2020: 176). Some of these voices sang the first open lesbian love songs, for instance Teresa Trull “I´d Like To Make Love To You”, the opening song on her album The Ways A Woman Can Be (1977). Other lyrics remained polysemic like Silvia Kohans “Taking my Baby up Town” (1984). The stanzas tell of experiences of discrimination: Insults in the park when she walks with her sweetheart in her arms, staring people when they kiss. Yet the gender of the lover is unspecified, listeners can also imagine racial or other reasons for this harassment.

Thus one can say the intention of reaching many women is encoded in the sound and semantic openness of much of the music while insiders hear the women´s music context in the low register of the voice and in references towards lesbian experience. For the contemporary feminist scene it proved that women can do it all on their own (a central ambition of the independent in general): compose, produce and market records equal in quality to the dominant male record industry. With its mainstream compatibility in sound, the music carries a claim: we are not different, we are just like everyone, we are normal. It claims participation and respect. This interpretation is supported by the fact that the collector did not store these records as a separate genre (as she did with Jazz and Blues) but as part of female pop music. Here strong women prevail: artists like Odetta, Joan Armatrading, Aretha Franklin and second-generation lesbian artists like k.d. lang and Tracy Chapman. Another example: the duet “Sisters Are Doing It For Themselves” by Annie Lennox (The Eurythmics) and Aretha Franklin is featured twice in the collection, on the self titled album The Eurythmics and on Aretha Franklin´s Who´s Zoomin’ Who?. Both albums in the collection as original pressings from 1985. This seems to be an important song for the collector.

Lesbian identity and women´s emancipation can be seen as two strong, permanent topics within the female pop part of the collection. Collecting women´s music might have been part of the collector’s general lesbian cultural identity. Completeness concerning records that are associated with this identity might explain the many shrink-wrapped albums in women´s music and from other artists that are somehow linked with queer identities, for example David Bowie with his androgynous, gender-bending style. They are statements of queer identity put in the collection together with the other male artists. Here, among the male artists too, a claim of queer equality is acted out in ordering the records this way.

Concerning the shrink-wrapped records the heir has an additional explanation: maybe the collector did not find time to listen to the records because she valued live music much higher than recorded music. She even registered a company to publish unedited live recordings of her favorite classical musicians. According to the heir, this effort failed because the musicians did not wish to publish live recordings with their inevitable imperfections.

This statement shows that the general attitude of the collector towards music might play into the collecting strategies, too. There are only few live recordings in the pop part of the collection yet this aspect must be considered when exploring the classical part of the collection.

Visibility of Women´s Music today

Lont reports that women´s music was widely ignored by the music press. It was only mentioned in lesbian and gay publications. Even in the 1980s, when a second generation of lesbian artists like Tracy Chapman and k.d. lang became successful on the mainstream market, the beginning of their careers in the women´s music scene remained unmentioned in the music press (Lont 1992). How is this past represented today on the internet, on websites that are part of canon formation processes like Wikipedia and Discogs? On Discogs, most records of women’s music are offered for very little money. Even the ones that were only released in small editions. Rarity is one possible condition for high prices yet there must be a demand. For those records, there is none. Furthermore, there is no category (neither genre nor style) women’s music on Discogs. It seems like women’s music is not noticed as a genre and not being collected. Thus once again subject of othering leading to invisibility, as is the case of women-composers (Myers 1998, Pendle ([1992] 2001). This may reflect a collector market that is dominated by the hetero male.

On the English Wikipedia site there is an article on women´s music[1]. It defines women´s music as a genre linked to the second wave feminist movement and a music market that thrived in the 1970s and 1980s USA. The article links to some of the central musicians, too. But it is different the other way around: on Discogs and Wikipedia there are mostly only short entries about the female musicians. There is almost no mention if they transported feminist or lesbian content in their music. The lesbian / feminist part of this music history is only told on a few marginal websites dedicated to LGBTQ+ music history.[2] Take as an example Mary Watkins: central as a musician and especially as a producer. The Wikipedia entry does not mention her role for women’s music at all.[3] It is different with Cris Williamson: while Discogs features no information but links to her homepage and the Wikipedia entry, the Wikipedia article points out the context of women’s music.[4]

It seems like today women´s music has become marginal in the history of popular music despite its undisputable contribution for widening women´s possibilities on the music market, preparing second generation artists like k.d. lang and Tracy Chapman for international success and establishing aesthetic novelty with the butch voice (Geffen 2020). The 1990s riot grrrls in contrast did not know anything about women´s music. They started from scratch without role models (Goldman 2019). Such silencing stands in the context of an overall trend not to give female artists legacies the same attention as their male counterparts. It leads to an exclusion of women´s music from the history of popular music. The „writing out“ of marginalized people and their music stories is (in)visible in women’s music on the Internet.

One counter argument here is that the process of canonization is bound by musical style as Nico Thom (2011) shows for popular music magazines. This might be true for particular stakeholders in the process. On the other hand, Anne Danielsen (2008) points out that songs might become canonical because they are experienced as good music across particular style or subcultural boundaries. So were those women´s music songs just not remarkable enough, or experienced by too few people, to form a lasting subcultural legacy? If you listen to the frantic audiences shouts in a live recording of the all women jazz band Alive! playing the song “Wild Women Don´t Get The Blues” on the album Call It Jazz (1981 and part of the collection) it becomes audible that the music was very important for the feminist culture of the time. More important than stilistic diversity seems to me that the women´s music background was already unmentioned in the promotion of many, especially the second generation lesbian musicians. In short, the more popular women´s music artists became, the more invisible women´s music became, because wider audiences should not be confronted with the controversially discussed activism of feminism or non-straight sexuality.

Rock Music?

The heir reports that the collector often spoke of how important rock music was to her. On the other hand genres of rock music that are today considered central for the 1960s to 1980s popular music are missing in the collection: progressive rock, psychedelic rock, hard rock. Reports from female fans and musicians show that such rock music was not only made primarily by men, it was also implicitly aimed primarily at men (Rohkohl 1979, Albertine 2015). Access to this world of rock music was not easy for girls.

The challenge here is to reconstruct the collector´s definition of rock music. As a first step, we can approach the general understanding of rock music among collectors today. If we take the database of the collection as a starting point we can ask: to which musicians in the collection do collectors on Discogs assign the attribute rock music? In the Discogs database, 22 of the male artists and 17 of the female artists are labeled with some kind of rock genre or style. This includes artists like Cindy Lauper, Michael Jackson, David Bowie, Rickie Lee Jones and Paul Simon. They are labeled as Pop Rock on Discogs. Other labels found in the Discogs database are Soft Rock (Bill Champlin, Maria Muldaur), Folk Rock (Joan Armatrading, Simon & Garfunkel, Tracy Chapman and others) or Classic Rock (Steely Dan). There is a gender bias among the styles: more female musicians are labeled Folk Rock and no female musician is labeled Classic Rock.

The collection prominently features acts that are attributed with crossover rock genres, mixing rock with jazz, folk or pop as well as artists who have an independent or dissident image within popular music like The Police or David Bowie. Explicitly male, hetero-sexually branded rock music from the genres core is largely missing in the collection. There are some notable exceptions though. Steely Dan is very prominent in the collection and some other rock artists appear with one album: The Rolling Stones, Bruce Springsteen, Van Halen.

The genre and style definitions from Discogs appearing here reflect that the overall genre rock was used in a very broad sense in the 1970s and 1980s. Some authors used it to label all popular music that is different from the (commercial) mainstream. Simon Frith points out that the core of rock aesthetics focuses on individual artistic expression. “Good [rock] music is the authentic expression of something – a person, an idea, a feeling, a shared experience, a Zeitgeist. […] rock-star quality describes the power that enables certain musicians to drive something individually obdurate through the system.” (Frith 1987: 136) This statement about the combination of authentic (and in varying degrees deviant) expression and individual strength describes many of the artists’ public images found in the collection. From The Beatles to Cindy Lauper, from Cris Williamson to David Bowie. It fits to many artists who are not labeled as rock music on Discogs as well. Simon Frith´s definition of rock seems like a matching description of a sensibility the collector had towards music. It might explain the collector’s use of the word rock music and why rock music was important for her: an authentic and strong expression of individuality beyond social norms that constrict women and many others.

Alternative Popular Music Narratives

The collection has taken us down several paths so far. To the question of gender and record collecting, to female teenage Beatles fanhood, to the now little-known domain of women’s music, to definitions of rock music and to the question of how the marginalization of subcultures that drove social transformation processes is perpetuated today. The collection thus became a starting point for a multidimensional other version of pop music history that makes some voids and silences in the canon visible. Still we followed only some major strands. The collector’s love for baroque music, for women composers, for ethnographic recordings, for Jazz and Blues have yet to be uncovered. They hint towards a collector with a multidimensional interest in music and a lifetime occupation with classical and later baroque music.

The quest already shows, a collector will set his or her own priorities. These may relate to the canon in different ways. The collector follows different and partly overlapping collecting strategies: from fandom concerning particular artists, many of them canonical, to the socio-cultural concern of women´s equality that leads to an emphasis of collecting musicians that are related to feminism, her own participation in the lesbian and feminist scene and to non-macho, fluid or transgressive masculinity. A biographically shaped, individual pop historiography becomes accessible through the material presence and traces within the collection. Strands of popular music may become visible that are underrepresented in the canon. The historiography within this collection shows that the modes of listening of white, male listeners dominate in the canon and that these have a strong influence on the writing of history until today. The marginalization of certain social groups (here, the feminist-lesbian scene) in the past is thus perpetuated today. The “filtering mechanism at work in the process of canon formation”, as Danielsen (2008: 18) calls it, demands further attention and analysis.

Concerning the forensic cultural studies approach we learned that the materiality of the collection includes the order and presentation of the collection by the collector. It is crucial to retrieve and document as much information as possible when accessing a collection for the first time. In the best case the collection should be accessed in its original state and the interior design it is placed in, including playback and listening arrangement. In retrospect we could only reconstruct some central elements of this situation. Pfleiderer (2011) in addition points to the importance of secondary material such as music magazines, books, posters and other music related material. Unfortunately, none of this was available in this particular case.

Overall, researching record collections is a promising endeavor revealing multiple narratives of popular histories, many of which are underrepresented in the common discourses on popular music today.

On the Author

Holger Schwetter, Dr., studied musicology and media science at the University of Osnabrück. In 2014 he received his PhD at Kassel University. His research focuses on sociology and music analysis of popular music cultures, working conditions in the music market, private music archives, and copyright in the cultural and creative industries. He currently works as a researcher at the Institute of Music at the University of Kassel and as a culture developer at the Municipality of Osnabrück. He is also second chairman of the Gesellschaft für Musikwirtschafts- und Musikkulturforschung (GMM).

Annotations

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women’s_music accessed 2022-07-04.

[2] Cfi. Queer Music Heritage, https://queermusicheritage.com/index.html accessed 30th of September 2021.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Watkins accessed 2020-02-18.

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cris_Williamson accessed 17th of September 2021.

List of References

Albertine, Viv. 2015. Clothes Music Boys. A Memoir. First paperback edition. London: Faber and Faber.

Elster, Christian. 2021. Pop-Musik sammeln: Zehn ethnografische Tracks zwischen Plattenladen und Streamingportal. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

Frith, Simon. 1987. “Towards an Aesthetic of Popular Music.” In Music and Society: The Politics of Composition, Performance and Reception, edited by Richard Leppert and Susan McClary. Cambridge.

Gamble, Christopher N., Joshua S. Hanan, and Thomas Nail. 2019. “What Is New Materialism?” Angelaki 24 (6): 111–34.

Goldman, Vivien. 2019. Revenge of the She-Punks: A Feminist Music History from Poly Styrene to Pussy Riot. University of Texas Press.

Jones, Carys Wyn. 2008. The Rock Canon: Canonical Values in the Reception of Rock Albums. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Kreutziger-Herr, Annette, and Katrin Losleben, eds. 2009. History – Herstory: Alternative Musikgeschichten. Köln: Böhlau.

Myers, M. 1998. “Musicology and the ‘Other’. European Ladies’ Orchestras 1850-1920.” In Gender Studies & Musik: Geschlechterrollen und ihre Bedeutung für die Musikwissenschaft, edited by Stefan Fragner, Jan Hemming, and Beate Kutschke. Regensburg: ConBrio-Verlagsgesellschaft.

Lont, Cynthia M. 1992. “Women´s Music. No Longer a Small Private Party.” In Rockin’ the Boat: Mass Music and Mass Movements, edited by Reebee Garofalo, 241–53. Boston, MA: South End Press.

Paz, Eilon. 2014. Dust & Grooves. Adventures in Record Collecting. New York: Dust & Grooves Publications.

Pendle, Karin, ed. 2001. Women & Music: A History. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press.

Pfleiderer, Martin. 2011. “Populäre Musik und Kulturelles Gedächtnis. Zur Einführung.” In Populäre Musik und Kulturelles Gedächtnis: Geschichtsschreibung – Archiv – Internet, edited by Martin Pfleiderer, 9–24. Köln: Böhlau.

Rohkohl, Brigitte. 1979. Rock-Frauen. Rororo 4454. Reinbek b. Hamburg: Rowohlt.

Sánchez-Olmos, Cande, Tatiana Hidalgo-Mari, and Eduardo Viñuela. 2021. “Brand Placement and Gender Inequality in the Top 30th Billboard Hot 100 from 2003 to 2016.” In Musik und Marken, edited by Lorenz Grünewald-Schukalla, Anita Jöri, and Holger Schwetter. Musikwirtschafts- Und Musikkulturforschung. Springer.

Straw, Will. 1997. “Sizing Up Record Collections: Gender and Connoisseurship in Rock Music Culture.” In Sexing the Groove: Popular Music and Gender, edited by Sheila Whiteley, 3–16. London: Routledge.

Thom, Nico. 2011. “Aktuelle Prozesse der Kanonbildung in multimedialen Magazinen der Populären Musik.” In Populäre Musik und Kulturelles Gedächtnis: Geschichtsschreibung – Archiv – Internet, edited by Martin Pfleiderer, 65–81. Köln: Böhlau.

Vinyl Records

Al Di Meola. 1983. Scenario. Vinyl Album. Vol. FC 38944. USA: Columbia.

Aretha. 1985. Who’s Zoomin’ Who? Vinyl Album. Vol. AL8-8266. USA: Arista.

Cris Williamson. 1975. The Changer And The Changed. Vinyl Album. Vol. LF904, reissue. USA: Olivia Records.

David Bowie. 1980. Low. Vinyl Album. Vol. AYL1-3856, reissue. USA: RCA.

Debbie Saunders. 1984. A Shot In The Dark. Vinyl Album. Vol. SBS 1011. USA: Step By Step Records.

Eurythmics. 1985. Be Yourself Tonight. Vinyl Album. Vol. AJL1-5429. USA: RCA.

Gayle Marie. 1982. Night Rainbow. GM 001. USA: Gayleo Music.

Holly Near. 1981. Fire In The Rain. Vinyl Album. Vol. RR402. USA: Redwood Records.

Linda Tillery. 1977. Linda Tillery. Vinyl Album. Vol. BLF 917. USA: Olivia Records.

Linda Tillery . 1985. Secrets. Vinyl Album. Vol. BLF 736. USA: 411 Records.

Mary Watkins. 1978. Something Moving. Vinyl Album. Vol. BLF 919. USA: Olivia Records.

Mary Watkins . 1982. Winds Of Change. Vinyl Album. Vol. PA 8030. USA: Palo Alto Records.

Mary Watkins . 1985. Spiritsong. Vinyl Album. Vol. RR-8506. USA: Redwood Records.

Meg Christian. 1977. Face The Music. Vinyl Album. Vol. LF913. USA: Olivia Records.

Meg Christian. 1981. Turning It Over. Vinyl Album. Vol. LF925. USA: Olivia Records.

Midler, Bette. 1873. Bette Midler. Vinyl Album. Vol. SD 7270. USA: Atlantic Records.

Silvia Kohan. 1984. Finally Real. Vinyl Album. Vol. DC-3003. USA: Dancing Cat Records.

Sweet Honey In The Rock. 1976. Sweet Honey In The Rock. Vol. FF 022. USA: Flying Fish.

Sweet Honey In The Rock . 1978. B’lieve I’ll Run On…. See What The End’s Gonna Be. Vol. RR 3500. USA: Redwood Records.

Sweet Honey In The Rock . 1981. Good News. Vol. FF 245. USA: Flying Fish. Sammlung Shelley Mesirow.

Teresa Trull. 1977. The Ways A Woman Can Be. Vinyl Album. Vol. LF 910. USA: Olivia Records.

The Beatles. 1964. Meet The Beatles! Vinyl Album. Vol. ST-2047. USA: Capitol Records. ———. 1965. Rubber Soul. Vinyl Album. Vol. ST-2442, Pinckneyville Pressing. USA: Capitol Records.

Proposal for Citation

Schwetter, Holger. 2022. „‘Finally Real‘. The Vinyl Record Collection of a lesbian Musician as an alternative Popular Music Narrative“ In Transformational POP: Transitions, Breaks, and Crises in Popular Music (Studies), edited by Beate Flath, Christoph Jacke and Manuel Troike (~Vibes – The IASPM D-A-CH Series 2). Berlin: IASPM D-A-CH. Online at http://www.vibes-theseries.org/schwetter-vinyl-collection.

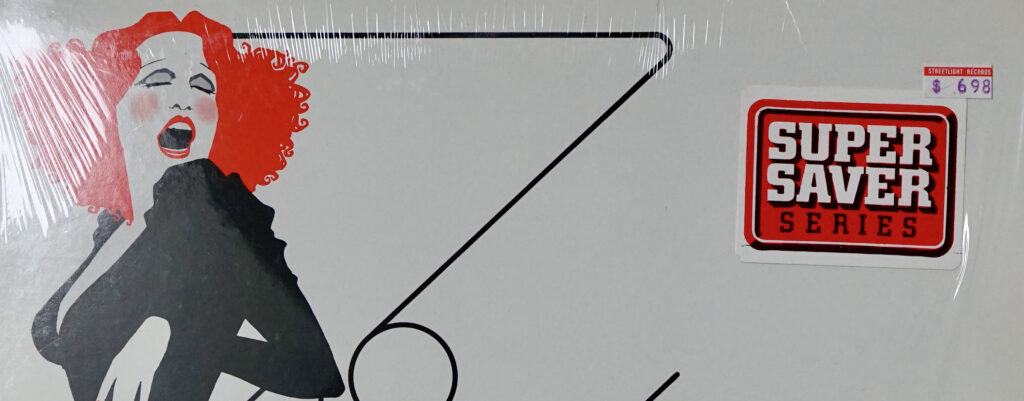

Cover Picture: Frontcover of the self-titled album „Bette Midler“. Scan by Holger Schwetter.

Abstract (German)

Während das Sammeln von Schallplatten eine anerkannte Praxis im Umgang mit populärer Musik ist, die hauptsächlich männlichen Sammlern zugeschrieben wird, ist die Forschung zu tatsächlichen Sammlungen selten. Dieser Artikel stellt eine forensische kulturwissenschaftliche Untersuchung der Plattensammlung einer Sammlerin vor, die in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren in den USA eine klassisch ausgebildete Musikerin und LGBTQ+ Aktivistin war. Ausgehend von der Materialität der Sammlung werden Spuren von Gender, Feminismus und lesbischer Kultur aufgedeckt und mit der Biografie der Sammlerin verbunden. Es wird deutlich, dass durch die Erforschung von Popmusikarchiven alternative, marginalisierte Popmusiknarrative sichtbar werden.